Kate Marrison in conversation with Markus Bassermann (October 2023)

The sharp rise in interest in the potential of digital media to preserve, revive and enhance Holocaust memory and education is intricately entangled not only with the passing of the survivor generation, but the emergence of new media technologies and the increasingly central role digital media play in our daily lives. The rapidly expanding list of augmented and mixed reality applications, cinematic virtual reality, digital mapping, photogrammetry, 360 degree-photography/video, 3D modelling, and interactive survivor testimony installations illustrates a momentum with no sign of slowing down. While there has been a tendency to privilege these types of projects over the last decade, digital games are beginning to receive increasing support from professional memory institutions and within the museum and heritage sectors more widely.

Critically exploring the shift underway, the Digital Holocaust Memory Project led by Victoria Grace Walden (University of Sussex), hosted a two-part webinar series titled Playing the Holocaust (Reframe, 2020, [online]), published blog posts (see Widmann, 2020; Marrison, 2020; Walden, 2021) and in partnership with the Historical Games Network has brought together a trans-disciplinary panel of academics, game designers, industry professionals and other stakeholders to create the report; Recommendations for Gaming and Play in Holocaust Memory and Education (Walden and Marrison et al., forthcoming). Notable participants to the webinars included Jörg Friedrich at Paintbucket Games responsible for the historical resistance sim Through the Darkest of Times (Paintbucket Games, 2020), as well as recent release Forced Abroad (2022) and The Darkest Files (forthcoming). As well as, Angela Shapiro, a founding member of Gathering the Voices, which has developed the game Marion’s Journey around the testimony of Marion Camrass (Chimera Tales, 2023). Luc Bernard also gave a presentation, tracing back his experiences since first proposing Imagination is the only Escape to arriving at his new game The Light in the Darkness (Epic Studios, 2023). It is noteworthy that since this discussion, Bernard has gone on to create Voices of the Forgotten, a “virtual Holocaust Museum” within Fortnite.1 Other important contributors to this field include Charles Games, a Prague-based indie studio which has produced Attentat 1942 (2017); Svoboda 1945: Liberation (2021) and Train to Sachsenhausen (2022).

For this blog post, I spoke with Project Manager, Markus Bassermann at the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres Commemorating the Victims of Nazi Crimes, about the forthcoming game, Remember. The Children of Bullenhuser Damm. The Bullenhuser Damm Memorial commemorates the 20 Jewish children and at least 28 adults who were murdered on 20 April 1945, by the SS in the basement of an empty school building. The children were abused for pseudo-medical experiments in the Neuengamme Concentration Camp before being taken to the school (for more see: The Bullenhuser Damm Memorial). Designed as a tablet application that can be used within classrooms, the digital game invites players to occupy the perspective of students within the school at Bullenhuser Damm in the late 1970s as they discover traces to the Nazi past and the crimes that occurred. The project is funded by the Alfred Landecker Foundation and created in partnership between the Foundation of Hamburg Memorials and Learning Centres Commemorating the Victims of Nazi Crimes and Paintbucket Games.

It starts with students asking…but what does any of this have to do with me?

“It’s an honest question” argues Bassermann and “it’s key” to this project. To ask how you are related to this history does not necessarily mean you don’t care but rather that you find yourself confronted with a past without really knowing why. Indeed, the concept for this project was born out of a need to facilitate an open and active discussion around this very question which enables young people to self-reflexively locate themselves within a greater whole, within cultures of remembrance.

Pupils (between the ages of 10-15) who will begin to learn about the topic in German schools and go on study visits to former sites of Nazi persecution are the primary target audience for the game. While some student groups will have the opportunity to visit the Bullenhuser Damm Memorial Site (situated less than 6km from Hamburg City Centre), Bassermann makes clear that “we didn’t want the game to repeat the content that is already there or act as a sort of clutch in relation to someone’s visit, we want the game to work on its own, as its own independent expression or media that is self-contained”. He clarifies, “so even if you’re teaching in Bavaria, you could still use it in the context of talking to your pupils about remembrance culture”.

Games and Holocaust Memory?

“The form of digital games has a very specific and unique language, and it’s a language we’re not currently talking in” asserts Bassermann. While he acknowledges the recent surge in interest or even “trend” in using new media technologies (such as AR/VR/XR) as novel modes of storytelling within the museum and heritage sectors, Bassermann underscores “the untapped potential” for games to be explored as vehicles for memory work. He argues, there is still “a certain conservativism” in attitudes towards games most often understood as a mode of enjoyment and entertainment which seemingly juxtaposes with the seriousness of the topic. Yet, he proudly proclaims, our team is “working from the opposite assumption [that the] two aspects work well together”, and there is potential in “marrying serious topics and interactivity and expressing something in this language”.

Prompted by this remark to discuss terminology, Bassermann agrees there is an urgent need to redefine and/or expand our vocabulary around games to arrive at more nuanced and critical understandings of what constitutes “play” within ludic environments and the potential for affective experiences therein. This work might mitigate the need to pitch similar projects as “serious games” in the hope of attracting funding and /or drawing critical and intellectual attention. Such caveats could in fact be counterintuitive for collective efforts across disciplines to take gaming seriously. Instead, sharing a desire to “coin a new genre”, Bassermann takes lead from Jörg Friedrich (Paintbucket) to arrive at the notion of a digital remembrance game. “It might not be a neat category like point-and-click-adventure” he admits, “but it’s an expression of what we are trying to do” which is specific to the central aims of the project while advocating for the affordances of the medium itself. To be sure, he argues that “serious games is a workable category […] but it’s an extremely poor category” in this context because it’s vague at best and evasive at worst; for example, “you could also have games which teach you how to become a certified forklift operator” under this umbrella term.

In any case, such qualifications are hardly necessary because, as Besserman reminds us, “everything is already being said, there are mainstream FPS games like Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014) which includes a level in a concentration camp [albeit a fictious location in the 1960s], everything can be said and is being said”. The interesting question, then, is not how this game may or may not trigger timeworn debates around the ethics of Holocaust representation, but rather how might it be “adding a voice” to an evolving gaming landscape that is, as several game scholars have noted, showing an increasing maturity and willingness to tackle moral themes.2

Playing with Memory

From the outset, Bassermann reports, “we had a certain confidence about talking openly” about what to include and exclude in the game. Attributing this to the trans-disciplinarity of the project team made up of game designers, developers, practitioners, historians, and professionals working within the memorial sites, he explains that they quickly decided not to base the narrative of the game during 1945 when the events themselves took place and not to base the characters on the historical figures of the victims. Rather, using archival materials and historical records as orientation points, the narrative is set in the late 1970s and invites the player to occupy a variety of personal perspectives through five students currently enrolled at the school. For context, it is important to note that in 1979 the first remembrance ceremony was attended by 2,000 Hamburg residents and the Children of Bullenhuser Damm Association was founded.

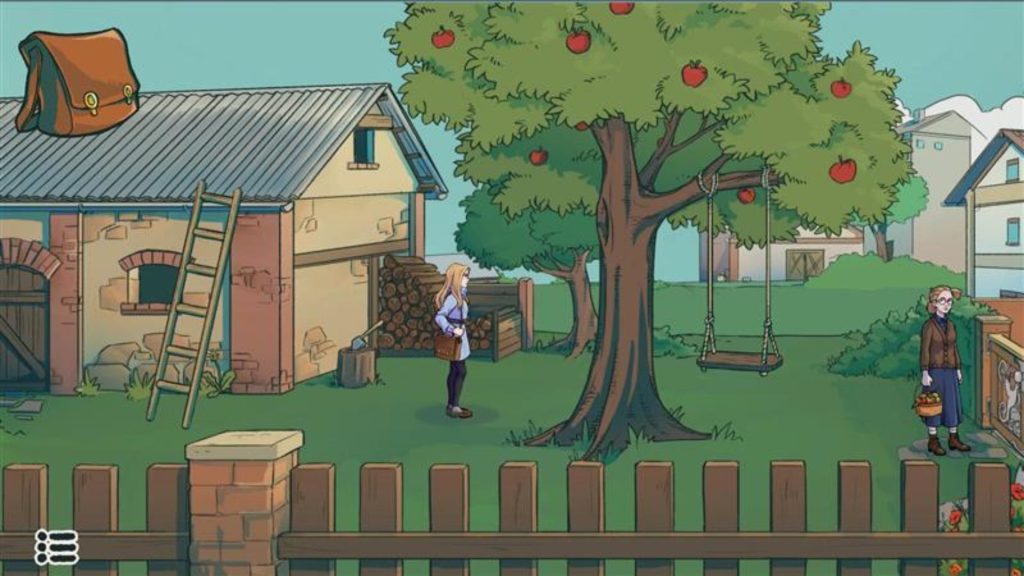

Echoing the vivid colour palette often associated with the decade, the game’s art style is marked by a distinctively bold design, which contrasts to the muted and greyscale undertones which often dominates the canon of Holocaust representation. The design team are also conscious of their use of symbols and Holocaust iconography in this regard, only integrating visual aids to evoke Holocaust themes as they pertain to specific elements of a character’s story (for instance including the graphic of a modern train which mutates into a wagon used for deportation to illustrate testimonial detail). In this way, this game goes further to place the topic of remembrance practices at its core, rather than the historical events per se.

Crucially, the positionality of the player is designed to parallel the student experience, encouraging the pupils to “recognise themselves” in the game across the spatial-temporal divide. To be clear, Bassermann confirms that they didn’t want to simulate the present day in which we have an established and arguably institutionalised memorial culture, but to transport players back to a time when commemorative practice around the events was fluid and still evolving. Indeed, he underscores the character case studies as the central conduit through which players can understand different socio-cultural and geo-political undercurrents which underpinned the emerging collective Holocaust imaginary in German society. While pupils have the choice to play through the protagonists’ stories in a non-linear fashion, taken together, the chapters form a multi-vocal, fragmentary, layered and even contradictory memoryscape.

Memory in Play

Perhaps most interesting is the way in which the game mechanics themselves articulate the often-paradoxical textures of memory. To illustrate this point Bassermann shares an example of a Polish student whose story begins with asking her grandmother for the recipe of an apple-pie. As her grandmother’s train of thought lapses into a memory of an apple tree, she ambiguously refers to her experiences within the Radom Ghetto during the war. Against the backdrop of the wider game narrative, the player can exercise agency by opting into dialogue with NPCs who can add further insight into the contextual framing of the family story. For instance, the protagonist can pose questions to her mother, consult newspapers, and even converse with an historian at the library.

Thus, there is potential for the “procedural rhetoric”3 of the game to communicate something not only about the nature of memory (and in this case intergenerational acts of transfer) but also implicitly issue statements about the value of testimony and historical sources respectively. To be sure, the character’s seemingly mundane actions (tapping the interface) motivate narrative progression on the one hand, while at the same time exposing more gaps in the story which ultimately lacks closure. In doing so, the game reemphasises the importance of testimony (particularly at a time when the eyewitness accounts are dwindling) and captures the residual, messy essence of memory which will always have a fundamental role to play in shaping our cultures of remembrance.

You can read more about the project via the Alfred Landecker Foundation.

Notes

- For more on Voices of the Forgotten see: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/16/arts/design/fortnite-holocaust-museum.html ↩︎

- W. Benedetti, (2010). Video games get real and grow up. [Online]. [Accessed 4 December 2022]. Available from: https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna36968970; M. B. Oliver and N. D., Woolley, J.K., Rogers, R., Sherrick, B., and Chung, Y. (2015). Video games as meaningful entertainment experiences. Psychology of Popular Media and Culture. 5 (4), pp. 390-405. ↩︎

- I. Bogost. 2007. Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames. Cambridge: MIT Press. ↩︎

Dr Kate Marrison is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Weidenfeld Institute of German-Jewish Studies, University of Sussex, where she is currently leading the ‘Sussex Digital Holocaust Education Project’ and working on the ESRC-funded ‘Co-creating Recommendations for Digital Interventions in Holocaust Memory and Education’ and the HEIF-funded ‘Dealing with Difficult Heritage’ projects. Her research is primarily focused on digital memory practice, education and commemoration as it emerges at the intersection between Holocaust studies and media theory. Prior to this, Kate worked as a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Leeds, where she also completed her PhD project, which explored the concept of digital witnessing across a range of case studies including virtual and augmented reality projects, video games and 3-dimensional installations of Holocaust survivor testimonies. Her research has been published within Jewish Film and New Media and has contributed to the edited volumes, Digital Holocaust Memory, Education and Research (Walden, 2021) and Visitor Experience at Holocaust Memorials and Museums (Popescu, 2023).

Markus Bassermann is the project manager and coordinator of this two-year project. After completing his Master’s degree in History at the University of Hamburg, he has been working on, amongst other things, the overlap between digital games and history as part of the History and Digital Games workgroup, as well as the Games and Memory Culture database. He is particularly interested in using the potential of such media through a strong integration of game mechanics and narrative. In addition to his work as a historian, Markus Bassermann also has experience in programming and is particularly looking forward to having the opportunity to expand his theoretical reflections in a practical way within the framework of the project. In addition to this, he works at the Hamburg Cooperative Museum and is involved with the digital history magazine Hamburgische Geschichten.