In 2022, the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in London opened ‘War Games’, an exhibition about video games and war, which it was my privilege to curate. Focussing on how video games tell stories of war and conflict, the exhibition featured a range of games, with contributions from their developers and historic artefacts from the museum’s collections. One game featured was Aardman Animation and DigixArt’s 11-11: Memories Retold (2018), an interactive narrative set in the First World War. The game tells a fictional story of a young Canadian photographer and an older German engineer whose fates entwine in the course of the war. Asked by the Historical Games Network to write on the theme of ‘Memory’ in historical games, it was this game that first sprang to mind.

11-11: Memories Retold was published amid commemorations that attended the centenary of the First World War, which Australian scholar Joan Beaumont called a ‘memory orgy’.1 With that conflict existing as a lingering trauma in the British historical imagination, and resonating deeply across Europe and the wider world, Memories Retold hits a nerve. The game was released on 11 November 2018, as countries around the world marked the centenary of the Armistice of 1918, a ceasefire which ended the fighting on the western front. The game’s launch was marked with a party at the Imperial War Museum, and the museum could claim a tiny role in bringing the game about; in 2014 IWM had commissioned Aardman Animations to produce a short film, Flight of the Stories, to advertise the museum’s new First World War Galleries. That film caught the eye of game director Yoan Fanise, who had previously developed Ubisoft’s heartbreaking First World War puzzle-platformer Valiant Hearts (2014), and would lead to Fanise’s company DigixArt collaborating with Aardman on 11-11: Memories Retold.

11-11 Memories Retold adopts an art style described by its developers as a living painting. The game presents a full-screen particle simulation, giving the impression that each scene is an oil painting being continuously reworked as the player explores the game world. This gives the game a fleeting, ethereal atmosphere that strongly complements the game’s narrative presentation of the protagonists’ memories of the war. While at times tending to lean on familiar images of the war, the game’s presentation powerfully evokes the war’s own place in our collective memory; with our living links to the Great War severed by the deaths of the last living witnesses in the 2010s, the war now only exists only in our shrouded and shifting memories.

Other games featured in my exhibition might also speak to our memories of different historical conflicts. Sometimes these memories overlap; in Polish company 11bit studios’ survival game This War of Mine (2014), developers were inspired directly by magazine accounts of the siege of Sarajevo during the Bosnian War of the 1990s, and less directly by shared family memories of the Second World War and life in Nazi-occupied Warsaw. This War Of Mine purposely demonstrates how gruelling life would be under siege or occupation, and compounds this with relentlessly bleak aesthetics. Pointedly reminding us that most people affected by war are civilians, This War Of Mine offers an important corrective for a medium largely addicted to the theatrics of gunfire, fireworks and macho superheroics. When I interviewed 11 bit’s staff for the exhibition, they were painfully conscious of a war brewing on their country’s borders; we spoke just weeks before Russia’s unprovoked invasion of neighbouring Ukraine, and at the time of writing it is impossible not to be horrified by images of civilian suffering coming out of Israel and Gaza.

Aside from specific reference points, more widely shared memories of war and conflict shape how developers approach the subject in their games. As part of the initial run of the exhibition, we included a room of playable retro games, appearing on original hardware. Among the games featured here was Sensible Software’s 1992 game Cannon Fodder, a game which sparked controversy when it launched. Cannon Fodder used the iconography of the red remembrance poppy both in-game and in its marketing. Appearing alongside the strapline ‘War Has Never Been So Much Fun’, the combination provoked the ire of parts of the tabloid press, who considered the game an insult to Britain’s war dead. At the time, with video games widely considered to be just one more corrupting influence on young people, the game’s satirical purpose was missed. Speaking with developer Jon Hare, he stressed the personal and cultural background from which the game emerged. Born in 1966, barely twenty years after the Second World War, Hare perceived the Britain of his early life to still be very much in a post-war phase, and identified the influence of the war’s place in popular culture on his work, such as war adventure comic books and television comedies like Dad’s Army and Blackadder Goes Forth.

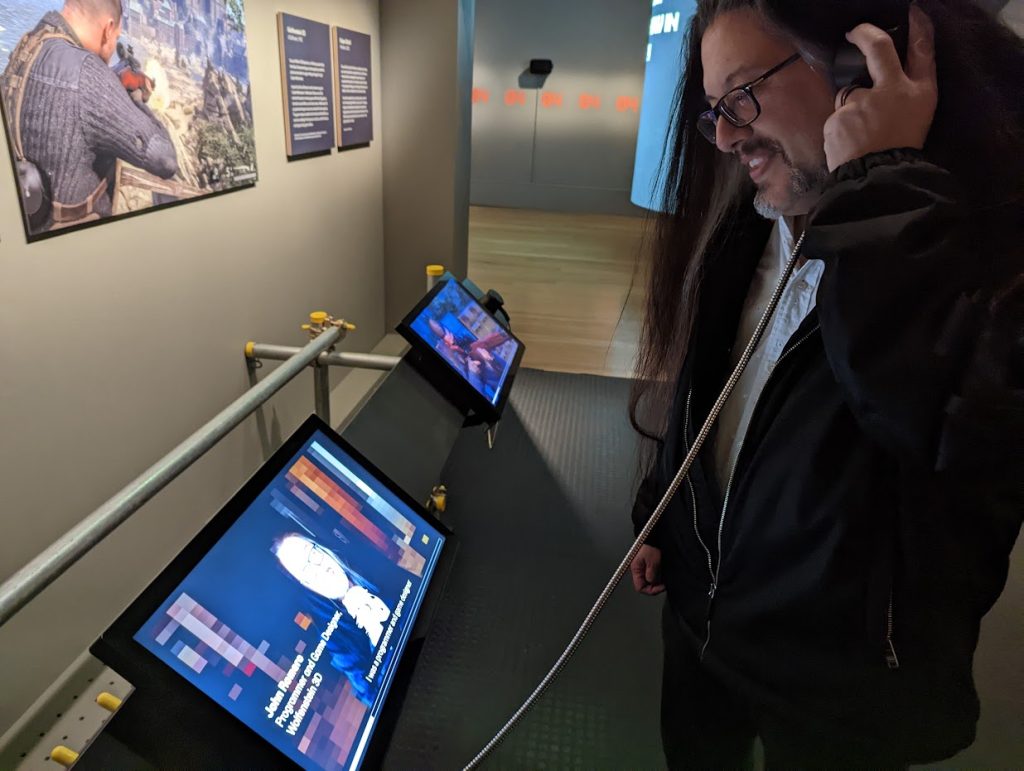

Cannon Fodder might also prompt us to consider how games engagement with the past can elicit responses from unexpected audiences, and how makers consider their audience at the outset. Among the shooters featured in the exhibition was Wolfenstein 3D. Speaking with former id Software developer John Romero, he described his surprise and satisfaction that among the voluminous fan mail id received following Wolfenstein’s launch, were letters from young Jewish players who found an intense satisfaction in slaughtering the game’s virtual hordes of Nazi stormtroopers.

At the moment of Wolfenstein 3D’s (1992) release, the Holocaust was re-emerging in the public consciousness, a process reflected in the release of Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film Schindler’s List. Spielberg has been a leading force in shaping the memory both of the Holocaust and the Second World War. His 1998 film Saving Private Ryan, and his television series Band of Brothers and The Pacific (and likely soon to be joined by his forthcoming series Masters of the Air) have strongly influenced the depiction of the war in other media, including in video games. Following the release of Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg conceived a video game, which would eventually release as Dreamworks Interactive’s 1999 Medal of Honor. Spielberg’s ambitions for the game reportedly included a desire that the game would reach the younger audiencebarred from seeing Saving Private Ryan in a cinema. Spawning multiple 3D Second World War shooter franchises, the influence of Medal of Honor has been profound.

This essay can hardly scratch the surface of the subject of memory in historical games. Games developers are influenced by the cultural moment in which they work, absorbing consciously or unconsciously the attitudes of their time towards different historical eras, and either consciously reshaping them, or allowing them to manifest themselves in their work. I’m drawn back to the origins of my War Games exhibition. The show had been inspired by an earlier exhibition, looking at war films and cinema. Surveying today’s landscape of, for instance, Second World War games, I’m mindful that at least some of their tendency towards action-adventure draws on a lineage that begins with the brassy, big-budget American war adventure films of the 1960s. It feels tempting to wonder how this landscape might differ if the starting point had been, for instance, the British war films of the 1950s, which tended towards a more intimate and less bombastic version of the war, written for audiences who knew firsthand how terrible the cost of war could be.

- Joan Beaumont, ‘Commemoration in Australia. A memory orgy?’, Australian Journal of Political Science 50/3 (2015), pp. 536-544. ↩︎

Ian Kikuchi is an Historian and Curator at the Imperial War Museum. After completing a BA in War Studies and History at King’s College London in 2007, he joined the Imperial War Museum film archive as a cataloguer. From 2011 to 2014 he worked on the museum’s First World War Galleries and since then has curated a number of exhibitions including Churchill and the Middle East and Real to Reel: A Century of War Movies. In 2016 he proposed War Games, an exhibition on war and video games. Opening in 2022 at IWM London, War Games explored how video games tell stories of war and conflict.