Imagine you are playing a game. Where are you? And does the location where you play shape your experience in any way?

The game experience always happens in a place, public and/or private [1]. There could be multiple reasons why you are playing in a private or public place, depending on the kind of game and the motivation behind playing. You also may not have much of a choice. Hjorth and de Souza e Silva note a 75% increase of online playing during lockdown as playing at home was often the only option [2]. Hence, more and more games were developed for this purpose, or even adapted. For example, Pokémon GO was temporarily modified to be played in proximity to a person’s house [2].

But if you are looking to immerse yourself in a game, then you will likely prefer to play in a safe and private place like your home, as immersion is “aided by privacy” [1]. If you are looking for a fun social activity and/or some leisure time outside the house, you may be more interested in playing in a public space. Pokémon GO was popular not only due to the fame of the Pokémon franchise, but also because it was fun to play with friends and it provided an opportunity to be outside [3].

While social motives and competition are strong motivators, not everyone likes the possibility of meeting new people by chance [3] [4]. Indeed, playing in a public space can lead to interacting with someone you don’t know and trust. Other people may also be watching. Indeed, playing in public spaces could be challenging for some people, even negatively affecting immersion. When Echo Games CIC* was collecting information for the design of a game to support young people within the youth justice service and care system, we realised the game needed to be designed for a private environment. Young people needed a safe venue without the stress of being watched over to engage.

Some public venues also face specific challenges. In my over 10 years of experience designing games and installations for museums, I discovered how important it is to learn more about the building and the room where the game will be located. For example, some museums are hosted in historical buildings where we may not be able to drill into walls or ceilings to install devices such as sensors or projectors. Creative solutions can be found, like building a fake column to hang (or hide) a projector. Other issues are not as easy to overcome. For instance, it’s not uncommon to visit an historical house and find out there is no WiFi and/or limited network coverage. Poor WiFi connection can be an issue if the museum plans to develop a mobile game or collect in-game data. Visitors would need to download the app before their visit and data would need to be stored locally. Another issue is maintenance, especially for digital games.

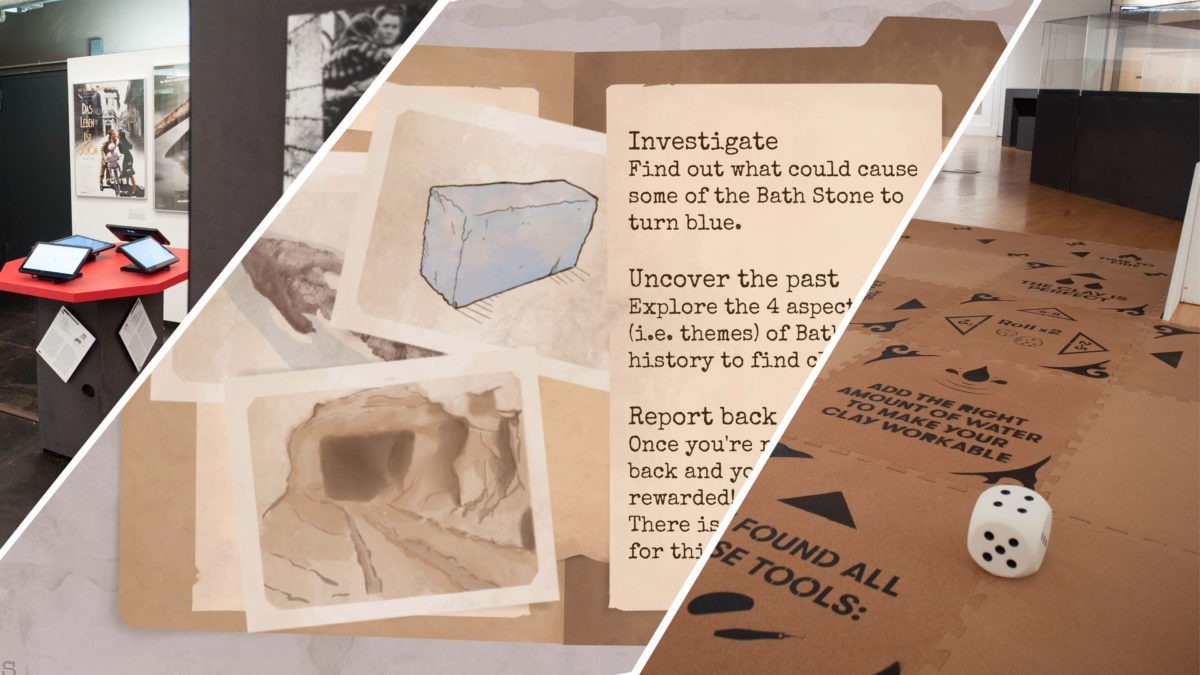

The Smithsonian institution confirms that digital technologies can benefit museums in many ways, but there are also problems, including maintenance costs by skilled technicians and constant upgrading [5]. Hence, digital installations may not always be the best solution for a museum. For example, when the Hunt Museum hired Echo Games to develop a game for “Made of Earth” – their exhibition on the story of clay and ceramics – we realised a digital installation would not have been a good fit. The museum also wanted to move towards more sustainable solutions. The result was “How on Earth”, a large floor-based experience where players embark on a journey to create a ceramic object. Players follow a floor path made by over 50 (hand-painted) cork tiles and interact with a series of interactive kiosks made out of reclaimed wood and metal.

Hence, the venue and its properties can influence both the design of a game and the play experience. As Lantz argues, the reason a game engages us or not may very well be external, related to the world that surrounds players [6]. This is why play is often all about location. When designing a game, it’s important to consider the relationship between game and venue from the very beginning. For instance, when I am hired by a museum to develop a game for a venue (e.g. a museum), I think about which kind of experience will fit in the space, taking into consideration the venue’s strengths and weaknesses but also its values and aesthetic. This was the case with “How on Earth”. When I consider the purpose of a game and the target audience, I think about which venue (private and/or public) will best match the game’s intentions. For example, online games can reach a wide audience and are flexible, meaning they can be played in a tranquil place like home or in a more public environment like school. Hence, online games can be a good solution for museums and cities that want to share knowledge with people all around the world. This is the case of “Unlock Bath”, a digital escape room Echo Games recently developed to engage players with the history of the city of Bath.

Thinking of where the game is played can be particularly effective for historical games. In general, the privacy of your living room would facilitate immersion while public locations may discourage you from playing. But with historical games, public spaces like museums or historical sites may bring extra value to the experience. For example, in Endless Blitz – one of the games we developed for the Ruhr Museum in Germany – players could put themselves in the shoes of a bomber whilst physically standing right in front of a display of original bombs from WWII [7].

Now, imagine you are playing an historical game like Assassins Creed or Battlefield V. Where are you?

*Echo Games CIC is the game company I am co-directing.

References

[1] Schell J. The Art of Game Design – A Book of Lenses. 2008

[2] Hjorth L and de Souza e Silva A, 2022, Playing with place: Location-based mobile games in post-pandemic public spaces. DOI: doi.org/10.1177/205015792211269

[3] Broom DR, Lee KY, Lam MHS, Flint SW. Go ta catch ’em al or not enough time: Users motivations for playing Pokémon Go™ and non-users’ reasons for not installing. Health Psychol Res. 2019 Mar 11;7(1):7714. doi: 10.4081/hpr.2019.7714.

[4] Alha K, Koskinen E, Paavilainen J, Hamari J, Why do people play location-based augmented reality games: A study on Pokémon GO,. Computers in Human Behavior. 2019. Volume 93: 114-122. DOI: doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.12.008

[5] The Smithsonian Institution Council Report: The Impact of Technology on Art Museums. October 2001.

[6] Steffen PW and Deterding S. The Gameful World. 2015.

[7] De Angeli D, Finnegan DJ, Scott L, and O’neill E. Unsettling Play: Perceptions of Agonistic Games. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2021. 14, 2, Article 15: 25. DOI: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3431925

Daniela De Angeli is the creative director of the community interest company Echo Games where she designs ‘seriously fun’ games that educate, stimulate critical reflection, bring awareness, tell important stories, and have a positive impact on society. Daniela has more than 13 years of experience as a game, graphic and interaction designer. She worked for museums and cultural organisations all around the world, including the New Mexico History Museum in the USA, The Ruhr Museum in Germany, the British Museum in the UK, the National Trust UK, and the National Geographic. Her works take theories from a variety of disciplines – from psychology and human-computer interaction to museology and memory studies – and translate them into game mechanics and narratives to fit different purposes.