Videogames offer us the possibility to create spaces to enjoy and engage with in ways that approach the past visually and interactively. We can play with history, and we can play to do history. But playing and history are also gendered.

Playing with history and gender can open possibilities for events that happened in a moment in human history and/or allow us to carry out counter-factual scenarios around what happened. These possibilities can be overrun by arguments and considerations of authenticity or accuracy (e.g., Salvati & Bullinger, 2013; French & Gardner, 2020; Manning, 2022). Whatever these terms – these “rules” – mean, they are weaponized to counter development of what can objectively be considered a depiction of society as something that has more than just men in it (Draycott, 2022).

To say that play, history and playing history are gendered may seem like an obvious statement, given that all of them involve people. However, as studies show (Draycott, 2022; Wells, 2023), arguments are being made that suggest this is not the case, reproducing colonial and imperial ideals of who gets to play. It is important to consider the presence of people when thinking about history, historical retelling, gender and videogames, mainly because they are either playing or (not) being represented.

This is not the place to review who gets to play and what ideas of gendered play and videogames exist (see, for example, Shaw, 2014; Ruberg, 2019; Chess, 2020; Gray, 2020, 2023). But I propose a moment of reflection on how we think about and engage with these spaces, and what we can do to create welcoming and diverse ones.

Playing between knowledge and perception

When thinking about games, history and gender, we need to question who appears, who is missing and what we consider when we look at it. This has several layers. Let’s begin with the first one. How do we recognize the people that are represented in videogames? Are we seeing diversity? Are we playing with gendered characters that both engage in representation of historical conceptions and contemporary negotiations of our historical understanding?

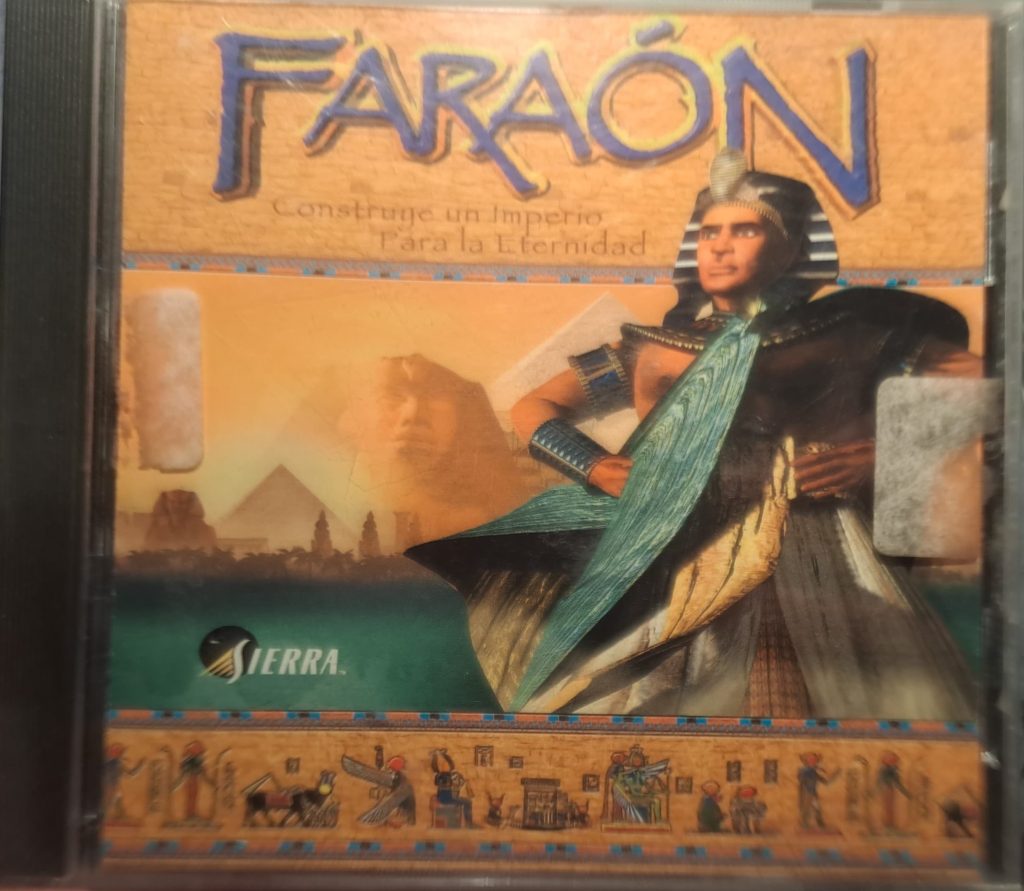

The answers to these questions are neither absolute nor completely settled. They will always sit in a realm of negotiation between our own perceptions of what happened, what we know of gendered constructions of the time, and what we know about our own time. A small example may help in making my point clearer. The original Pharaoh (Impressions Games, 1999) had NPCs taking care of day-to-day business that could be identified within the gender binary across the city being built. This presence provided background to player objectives, animated the city and offered as another mechanic for players to work with. It still reproduced our own (contemporary) gender stereotypes and gendered roles of care and manual labour, adding force to my argument. Women’s presence in the game was visible in different scenarios that ran across thousands of years of history. I will come back to this point later.

Citadelum (Abylight Barcelona, 2024) deals with a different society and different time but it carries our perceptions of gender into these historical settings. Women are harder to find in the cities being built. They appear when going to the entertainment activities the player provides and, if we are really looking, in the tavern(s). Once again, historically accurate presence, but also shaped by our perception of what they were doing. Any other work is carried out by models that can be recognized as men.

Any gender historian will probably be sighing by now. I know, you know, we know. We have had these conversations already. Both these games are from different moments, deal with different societies and in different times. However, they both reproduce a mix of our gendered perceptions accompanied by historical knowledge. Women worked in many of the activities that serve as mechanics in both games but are not represented there. Both games also span many years and that makes being able to cover every moment with historically accurate (I know you know) representation impossible. We have varied information across the thousands of years covered in Pharaoh but, for the period in which the Citadelumcampaign is set, we have plenty more information. Information that would have made women more visible throughout the cities the players build.

Both examples are less than a drop in the ocean of historically inspired games that we could discuss through the lens of gender. I chose them because most of the representation here is outside of players’ control. Players can choose where and what to place, but not what models will come out of those buildings or move around the city. They are not choosing to show more high-status women than lower status, nor are they choosing to just engage in reproducing the gender binary. These design options also build and reproduce what we think we know and what constitutes a common sense of a given period.

We may prioritize the idea of manual labour being a man’s job because of strength, we can decide that care is only feminine; and sometimes that is backed by our historical knowledge. Most of this has been contested extensively (Hemelrijk & Woolf, 2013; Campanile et al, 2017; Draycott & Cook, 2022) but it continues to reappear. Of course it will, given the ongoing questioning happening not only across the gaming world, but the world in general. Yes, we have had these conversations already (Chess, 2020; Martínez, 2020), and we will have to have them still. We are doing better, but we are still working within binary understandings and restricting our focus to how they are historically constructed instead of thinking about more diverse identities as they relate in their historical settings. We can still do better.

Thinking and exchanging about our playing

Videogames are a product of their time – of our time. The intermeshing of historical knowledge and our own perceptions will filter into them. But sometimes, a particular perception continues to appear. Maybe because it is easier. Maybe because it sells more. Maybe because. Part of that contemporary perception is also something that we need to question further. Thinking about how colonialist imaginary works (Rojas Mix, 2006) helps in our understanding of how we continue dealing with our biases and preconceptions. How we repeat the creation of games centred in one approach to history. We can aim to change that to representing and playing a history where the characters bring more diverse experiences across gender, status/class, race/ethnicity. We need to continue to test our own understandings of how colonial constructions continue to influence our historical knowledge, as well as our common perceptions of what can be done through its representation in videogames. History is complex, diverse and extensive. We cannot welcome representations through videogames that are any less than that, and we cannot expect our historical research to be less than that either.

I am aware I have opened more than one proverbial Pandora’s box (I know, too on the nose). My aim with this piece was not to have definitive solutions and answers. I don’t know we can have them, and maybe that is part of the issue in our attempts to create more complex historically gendered videogames. There is a lot of false certainty about how things were/are from particular exclusionary groups. What we can be certain of is that we do have our own definitive position: we need to turn from an ethics of death to an ethics of life (Dussel, 2006). History, gender and videogames can provide those experiences, because they allow us to play with history and play to do history. We need to engage in conversation to build these experiences in the future.

Leandro Wallace is a PhD Candidate in the Department of Critical Indigenous Studies Macquarie University, working across Critical Indigenous Studies, Gender and Queer Studies, History and Game Studies. His thesis works on queer Indigenous practices to counter colonial influences in and around videogames and screen media more generally, through a rights-based approach. It focuses on working around and through issues of representation, gameplay and enjoyment, and anticolonial development practices through Indigenous futurism. He is a member of En-Gender! as editor, conference organizer and cohost and coproducer of the “EnGender Conversations” podcast.

Ludography

Citadelum. 2024. Abylight Barcelona

Pharaoh. 1999. Impression Games.

References

Campanile, D. et al (eds.) (2017). TransAntiquity. Cross-dressing and Transgender Dynamics in the Ancient World. Routledge.

Chess, S. 2020. Play Like a Feminist. The MIT Press

Draycott, J. (2022). “A short introduction to women in historical and archaeological video games”. In Draycott, J. (ed.). Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games. De Gruyter.

Draycott, J. & Cook, K. (eds.) (2022). Women in Classical Video Games. Bloomsbury Academic.

French, T. & Gardner, A. (2020). “Playing in a ‘Real’ Past: Classical Actions Games and Authenticity”. In Rollinger, C. (ed.). Classical Antiquity in Video Games. Playing with the Ancient World. Bloomsbury Academic. 63-76.

Gray, K.L. (2020). Intersectional Tech. Black Users in Digital Gaming. Louisiana State University Press.

Gray, K.L. (2023). Killing the Black Body: Necropolitics and Racial Hierarchies in Digital Gaming. Filozofski vestnik. Vol. 44 (2). pp. 181-198. doi: 10.3986/fv.44.2.08

Hemelrijk, E. & Woolf, G. (eds.) (2013). Women in the Roman City in the Latin West. Brill.

Manning, C. (2022). “Assassins and the Creed: A look at the Assassin’s Creed series, Ubisoft, and women in the video game industry”. In Draycott, J. (ed.). Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games. De Gruyter.

Martínez, M. H. (2020). Feminist Cyber-resistance to Digital Violence. Debats: Revista de cultura, poder i societat. 5. 287-302.

Ruberg, B. (2019). Video Games Have Always Been Queer. New York University Press.

Rojas Mix, M. (2006). El Imaginario. Civilización y cultural del siglo XXI. Prometeo.

Salvati, A.J. & Bullinger, J. M. (2013). “Selective Authenticity and the Playable Past”. In Kapell, M. W. & Elliot, A. B. R. (eds.). Playing with the Past. Digital games and the simulation of history. Bloomsbury Academic. 153-168.

Shaw, A. (2014). Gaming at the Edge. Sexuality and Gender at the Margins of Gamer Culture. University of Minnesota Press.

Wells, G. et al (2023). Right-Wing Extremism in Mainstream Games: A Review of the Literature. Games and Culture, 19(4), 469-492.