There are staggering problems with historical games’ representation of women. Based on an analysis of games with identifiable protagonists from the HistoriaGames database, less than 7% of historical games have female protagonists, and more games feature plots in which women are abducted or killed to motivate the storyline than have female protagonists. Sexualisation and gratuitous nudity are rife, and women’s roles are limited and often negative, with narratives about women relying on (often misogynistic) stereotypes in lieu of meaningful characterisation or their agential roles in the plot.1 Even games which allow interchangeable-gender protagonists may make them entirely interchangeable, thus developing no engagement with any of the different experiences which women had in their historical settings.2 As a result, historical games rarely take advantage of their full potential to immerse players in a diverse, varied range of perspectives on the past, even just at this basic level of representing the ‘other’ 50% of the population.

Some games do attempt to invite players to reflect on historical experiences of gender through the creation of counterfactual histories which centre fictional women, for example the Expeditions series, all of which enable a female protagonist, and then make use of dialogue changes or minor quest differences to reflect on that choice, without limiting player enjoyment or agency.3 Many of these attach these hypothetical protagonists to real historical events, such as Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon, fictionalised in Expeditions: Rome (THQ Nordic, 2022). Banner of the Maid (Azure Flame Studio, 2019) similarly has as its protagonist a fictionalised Pauline Bonaparte, who fights battles associated with her brother’s campaigns. The plotlines and events in this game are not historical, but both she herself and many of the female characters in the game are historical figures, perhaps inviting research into their historical experiences even if the events of the game vary from historical accounts.4

However, it is clearly not the case that the only way to engage with women’s histories is to deal in counterfactuals, or to attach them as fictional alternatives to men’s better-known histories. After all, women were part of the past. For the remainder of this post, I will discuss another way in which historical games can and do engage meaningfully with gender through the exploration of women’s histories. Strikingly, the three recently released games I discuss here all take a microhistory approach and have smaller-scale settings, rather than representing events on the global scale often found in strategy games or even ‘heroic’ action RPGs.5 They are also all narrative-focused games. These smaller-scale settings seem to enable focus on the historical experiences of their female characters. Nonetheless, the settings and narratives of these games vary considerably, suggesting that this approach could be expanded significantly across the scope of represented history. If this style of historical game writing and design were more common, perhaps we would see significantly improved engagement with women’s histories, alongside a valuable diversification of what the nature of ‘historical gaming’ might entail.

Representing women’s histories

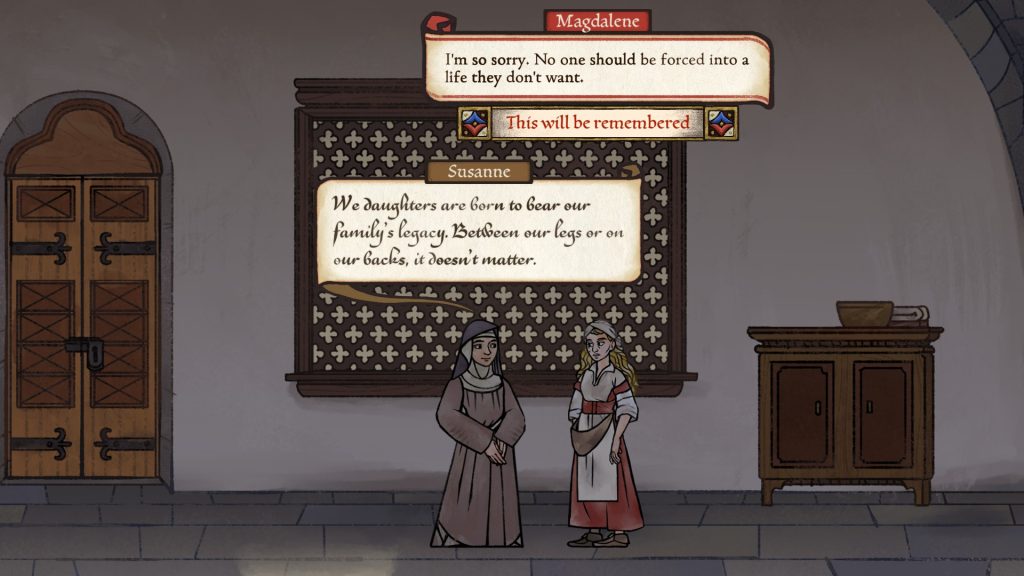

Women’s choices, and particularly the historical constraints around women’s choices are raised repeatedly for the player to consider in Pentiment (Obsidian Entertainment, 2022). This early modern game’s setting in a village connected to a large abbey and convent means that questions around women’s religious lives, among other issues, and occupational options are explored across the game. In the game’s final act the second protagonist, Magdalene, explores the convent, gaining access by pretending she is considering joining the order. During these scenes, she has the chance to consider her other options and understand why Susanne, her guide, has ended up among the Poor Clares. Even when the player plays as Andreas in the first two acts, his conversations with the sisters Iluminata and Zdena invite reflection on the ways in which economic or political choices made by their families had a huge impact on the way of life medieval women would be expected to follow, often against their own wills.

Similarly the setting of inkle’s Expelled! (2025), one day in a 1920s girls’ boarding school, has the effect of organically raising a range of considerations around women’s and girls’ educations, access to learning, and class dynamics, without any of these necessarily being a central purpose of the game. Conversations with the headmistress, Latin teacher Miss Lemon, and other girls explore the class dynamics and tensions in the provision of ‘scholarships,’ and thus broadening of education to a wider range of girls. This includes snobbery around regional difference at a time before widespread state education: for example, Verity’s Northern background is explicitly denigrated by both the headmistress and another student. Miss Lemon can also be asked about her own education, and the classical languages which she has learned from her missionary father’s educational plans for her (a common influence on girls’ access to education in the period). Experiences of sexuality in these settings (both “Sapphic”, as the headmistress describes one claimed assignation, and heterosexual) and the perils of underage, pre-marital pregnancy and lack of sex education are also explored through dialogue.

Just as Pentiment is not marketed as a game ‘about women’s history’, Expelled! does not purport to be a history of girls’ education, and Jon Ingold, its writer, has noted the influence of fictional school stories on its creation.6 Nor is the main plot focused on any of these issues, as the gameplay centres around Verity’s attempts to escape being framed for an attack on another girl. Nonetheless, the game neatly demonstrates how women’s and girls’ histories can be explored and become a topic of valuable reflection by players, even when this is not an explicit focus. Willingness to consider a wider range of settings and protagonists can organically introduce these issues into the player’s experience, and, in the process, provide a more inclusive and thoughtful approach to the past.

Finally, The Excavation of Hob’s Barrow (Cloak and Dagger Games, 2022) is another game with a tightly focused setting and a plot which takes place over a handful of days. Hob’s Barrow explores its female protagonist’s, Thomasina Bateman’s, excavation of a barrow in a rural Northern English village. Again the main plot of the game is not an exploration of women’s history – rather, the peculiar nature of Hob’s Barrow itself and the horror tale attached to it is the main narrative.

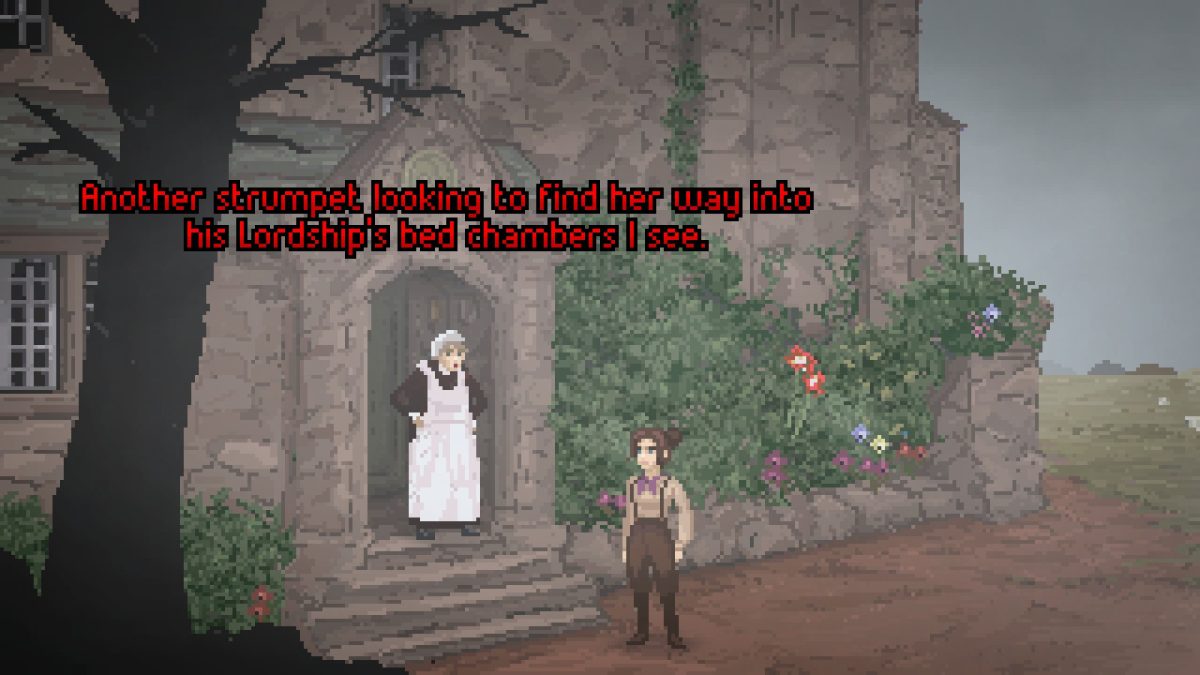

Yet by using a female protagonist in its 1800s setting, the game foregrounds in dialogue the experiences of its female antiquarian protagonist, including her experience of sexual harassment by a drunkard, and repeated comments on her appearance and marital status, arising from her apparently surprising decision to travel alone as a young woman. At the same time, some individuals clearly respect her expertise and research project, accurately reflecting how women were beginning to be able to be publicly involved in such activities in precisely the period of the game’s story. This game therefore reflects some of the early histories of female antiquarians such as Christian Maclagan, whose careers were often impacted by their experiences of sexism, but who nonetheless carried out major excavations and contributed significantly to archaeological and historical understanding across Britain.7 As a result, it invites players to reflect on these women’s histories, (at least until the horror elements of the narrative truly take over), and on the roles they themselves played in establishing British history.

Looking ahead

In the past few years of working on gender, women, and historical gaming, I have often been asked about alternatives to the bleak lack of representation in many games. Historical games could be doing a great deal more to engage with women’s histories, and to represent women and people of marginalised genders (often even more marginalised in these contexts), in more inclusive ways. As the games I have discussed demonstrate, fascinating stories across a wide range of histories can be explored by games which enable this kind of representation, particularly but not exclusively by narrowing down the scope of narratives to enable new areas of focus and new types of story. There is a great deal more to do to reverse the prevailing negative trend – but as these examples show, there are positive and exciting opportunities available in how historical games are written and designed, to make them a more inclusive representation of the past, and to explore a whole new realm of historical stories.

Kate Cook is a Lecturer in Greek Culture at King’s College London. Her research on video games focuses on gender in classical and historical video games, particularly the representation of women. She co-edited Women in Classical Video Games and is a co-editor for the forthcoming Routledge Companion to Video Games and History, and has works published and forthcoming on Roman women in Expeditions: Rome and Choices: A Courtesan of Rome, Persephone and agency in video games, women and sexism in historical video games and time travel in mobile games. She has also published on gender and language in Greek Tragedy.

References

- For more on the many problems with women in historical games, and more detail on the numbers quoted here, see my forthcoming chapter ‘Women and Sexism’ in the Routledge Companion to Video Games and History (2026). ↩︎

- Assassin’s Creed: Odyssey (Ubisoft, 2018) and Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla (Ubisoft, 2020) are clear examples. ↩︎

- See further: Kate Cook, ‘An Expedition into Agency: The Portrayal of Roman Women in Expeditions: Rome’. In Audio-Visual Roman Women: Gender, History & Screen Media, edited by Maria Wyke and Monika Wozniak (Bloomsbury, 2026); Marie-Luise Meier, ‘“The Hardest Battles Are Fought in the Mind”: The Role of Women in Viking Age Games’. In Women in Historical and Archaeological Video Games, edited by Jane Draycott (De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2022). ↩︎

- Looije argues for this kind of research inspiration as a benefit of the depiction of historical figures in historical games in Nathan Looije, ‘Exploring History through Depictions of Historical Characters in Assassin’s Creed Odyssey’. In ›Assassin’s Creed‹ in the Classroom: History’s Playground or a Stab in the Dark?, edited by Erik Champion and Juan Francisco Hiriart Vera (De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2023). ↩︎

- Wainwright argues that the prominence of these genres is a main reason for poor representation of women in historical games – there is no reason why strategy games (for example) should be inherently less inclusive, but the shared genre of the games discussed here is probably not insignificant. See A. Martin Wainwright,Virtual History: How Videogames Portray the Past (Routledge, 2019), 168–9 ↩︎

- Cressup, dir. Inkle’s Next Game Will Be ‘Overboard!’ Set In A 1920s Boarding School | Interview With Jon Ingold. 2024. 51:42. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9WGcLk29iYU; On Pentiment’s inspirations and sources, which were advertised as including historical materials, cf. Esther Wright. ‘“Layers of History”: History as Construction/Constructing History in Pentiment’. ROMchip 6, no. 1 (2024): 1. ↩︎

- Sheila M. Elsdon, Christian Maclagan: Stirling’s Formidable Lady Antiquary (Pinkfoot Press, 2004). ↩︎