A long time ago, in a world almost, but not quite, like our own…

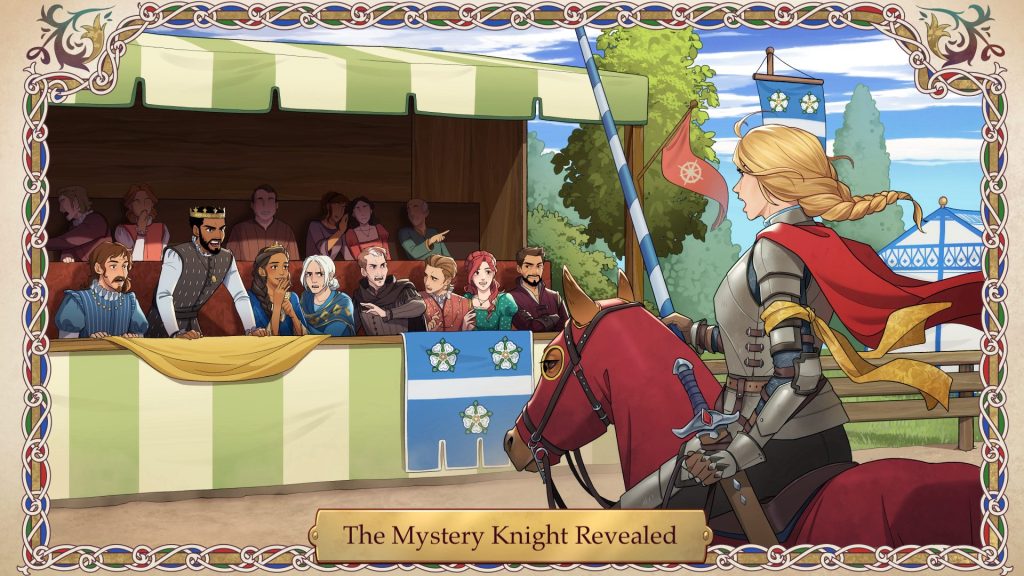

The city-state of Castamont, a centre of scholarship and commerce on the shores of the scenic Ousarine Bay, is buzzing with excitement! An anonymous knight, an armour-clad Mystery Knight who never removes his full-faced helmet, has arrived to joust in this year’s Grand Tournament! Rumours of great martial deeds and even greater chivalric valour already surround him, as does speculations about a very courtly romance between him and the brilliant and elegant Crown Princess Iris! But who is this mysterious knight really? Why has he sworn to hide his true identity? Which cause of honour has brought him to Castamont? And which boon will he request from Prince Vincenzo if he wins the Grand Tournament?

So begins the story of The Knight & the Maiden: A Modern Medieval Folk-Tale, a forthcoming comedic narrative adventure game with visual novel elements set in a secondary world inspired by our own world in the late 15th century. I have been working on this project for the last three years along with a team of talented freelancers, and it’s slated for release in late 2025 or early 2026.

After we introduce the Mystery Knight at the very start of the game, the player quickly learns that this enigmatic figure is in fact the noblewoman Charlotte Montfort, who has come to Castamont in search of her father, Sir Gilbert Montfort, who sits unjustly imprisoned in the Prince’s dungeons on false charges of espionage and treason. But rather than trust in the legal system of an unfamiliar city state and its political circumstances, she has instead decided to disguise herself as a knight by putting on her father’s old plate armour, win the city’s Grand Tournament, and use the boon traditionally granted to the winner to demand her father’s release! (At least that’s the plan. Charlotte thinks it’s a great plan! Her comrade in arms, the old squire Leofric, is less convinced).

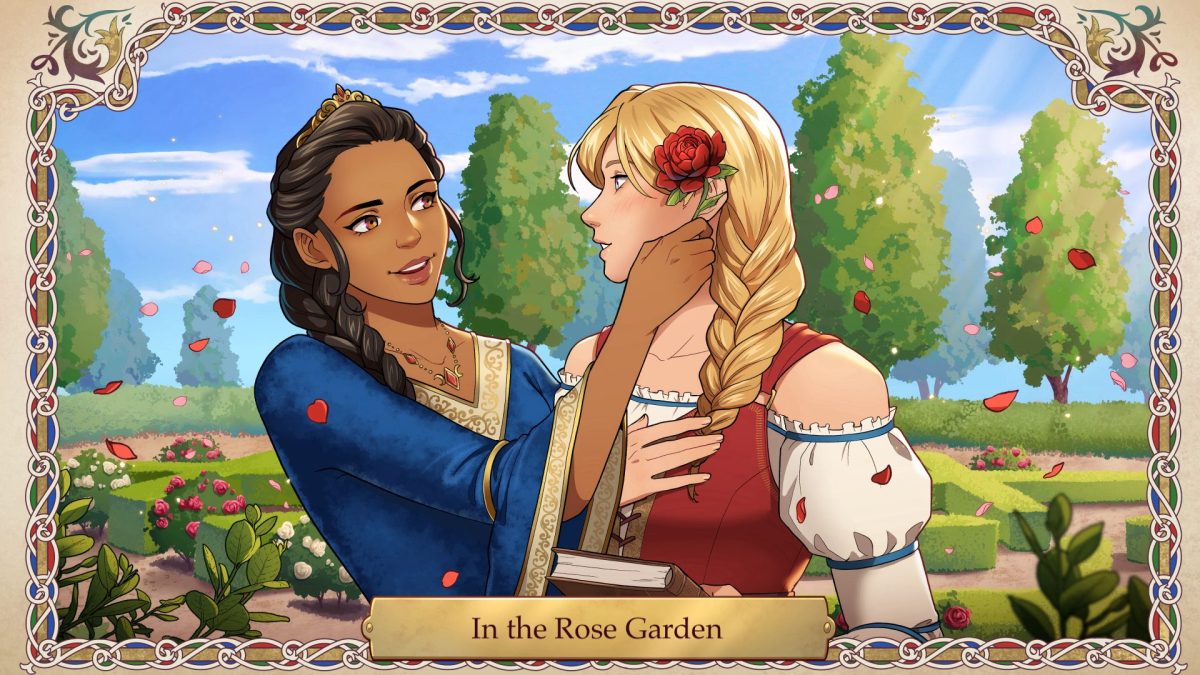

But the situation becomes even more complicated when she meets (and instantly falls in love with) the brilliant and elegant Crown Princess Iris of Castamont, while at the same time, two villains also lurk in the background: Master Lerwick, Castamont’s scheming spymaster, whose true allegiances are at best highly suspect, and the evil and arrogant Count Leogrance who plots to marry Princess Iris and annex the small principality of Castamont to the neighbouring kingdom of Lyonesse. The stakes of this adventure could not be higher!

The Duality of a Heroine

The gameplay is designed as a mix between a traditional adventure game and a visual novel in which the player must explore the game world, talk to the game’s characters, and solve puzzles to progress through the story’s seven chapters, each of which features a particular knightly opponent who Charlotte must defeat in the tournament. Although Charlotte is a talented jouster, she lacks the experience to match these seven professional knights, so instead she must use subversion to expose or exploit each opponent’s flaw in order to create a situation where she is able to defeat each one in the joust.

A central puzzle-solving mechanic involves Charlotte switching between her two personas (and occasionally other disguises) and taking advantage of the different ways that the game world and its characters respond to each one: some situations are better solved as the male-presenting and higher-status Mystery Knight, while others require the lower profile and charm of Charlotte herself.

But more than just being a convenient disguise, putting on the Mystery Knight’s armour reveals a degree of gender fluidity in Charlotte’s character – the change of external gender signifiers also brings about an internal change of personality, although in a way that to a degree inverts the “traditional” stereotypes of the confident and outgoing masculine character versus the retiring and self-effacing feminine character. In this case Charlotte is outgoing, impulsive and a bit snarky, whereas the Mystery Knight is much more formal, restrained, and socially awkward.

We use this dynamic partially for comedic effect – for example, showing how the Mystery Knight persona becomes so flustered when “he” meets Princess Iris that “he” can barely form a single coherent sentence, whereas Charlotte is perfectly comfortable having long conversations with the Princess – but it also adds complexity to Charlotte’s character and gender identity and emphasises the inherently subversive nature of her quest.

This relationship between the two parts of her personality evolves throughout the story, until by the end she finally needs to put aside the Mystery Knight disguise and step fully into the role of the female knight, merging the two and ultimately becoming an expression of Jack Halberstam’s concept of “female masculinity”, as Katie Vernon has recently discussed.1

Flawed Flowers of Chivalry

Meanwhile, the patriarchal system that Charlotte is up against is embodied by the seven opponents that Charlotte must defeat in the tournament, each of which is based on a common cultural/literary trope related to chivalry and knighthood, e.g. Sir Emmett the Courtly Lover, Sir Gareth the Questing Knight, and Count Leogrance the Power-hungry Noble. Rather than being “traditional” exemplars of honourable knights, these opponents are all deeply flawed individuals, ranging from those who are merely misguided to – in the later parts of the story – outright murderers and instigators of high-stakes political intrigues.

At the same time, Charlotte’s actions also reveal an inherent flaw in this society as a whole, as the vast majority of people in Castamont only see what they expect to see, taking the Mystery Knight’s identity completely at face value (or rather face-plate value). Indeed, only a few individuals – such as Princess Iris’s sceptical chambermaid Marigold and the cynical knight-for-hire Sir Matthis – are able to look beyond the Mystery Knight’s visible signifiers and suspect the real truth.

At the very heart of the story is the evolving relationship – and growing romance – between Charlotte and Crown Princess Iris, which in itself represents a subversion of the classic “knight in shining armour and damsel in distress” trope. While Iris is a damsel and definitely in some amount of distress due to the intrigues of the story’s villains, she is also a very active and powerful person in her own right who assists Charlotte and the Mystery Knight with both information and political support.

At the same time, this relationship also illustrates the potential personal costs of being an agent of subversion – to preserve her disguise, Charlotte must hide the true identity of the Mystery Knight even from Iris, and a central question of the story is whether their romance will survive the inevitable revelation of this untruthfulness.

In the end, though, as much as Charlotte liberally employs subversion and misdirection to achieve her aims, her quest is ultimately a search for justice and for truth – the truth about what has happened to her father, about the forces that threaten her lady Iris, and not least about herself and her place in the world.

Unfortunately, neither justice nor truth are obtainable by staying within her society’s boundaries of “acceptable” behaviour – in fact, were she to do so, the story’s villains would succeed in their plots and injustice would prevail. It is only by resorting to the “unchivalrous” methods of subversion that she can gain for herself the agency she needs to succeed in her quest and in the process force her society to change enough that, by the end of the story, she can finally put aside her disguise as the Mystery Knight and come fully into her own as Sir Charlotte, la bonne chevalière.

Gender as a Curated Medievalism

The story we tell in The Knight & the Maiden is not intended to be “historically accurate” in any sense – it is much more A Knight’s Tale (2001) than The Canterbury Tales (c. 1400) – but rather a story taking place in a secondary world that offers its own ‘authentic’ interpretation of the late 15th century. Our process for creating this world is very similar to what James Baillie has termed “curated medievalisms”,2 in which we pick references from a variety of medieval sources to establish the appropriate mental and cultural space within the game world.

The playful approach to gender and its representation in our story would have been very familiar to medieval audiences, judging from such narratives as Lancelot’s crossdressing in Le Morte d’Arthur, Ulrich von Liechtenstein’s jousting pilgrimage dressed as Lady Venus (as described in his Frauendienst), or the genderfluid Silence from Le Roman de Silence. Likewise, the late medieval tournament in particular seems to have offered a “space in which to push the boundaries of cultural norms”, such as the 1348 tournament described in Knighton’s Chronicle, at which a group of women adopted male dress and carried weapons to enact a kind of performative or playful transgression of gender norms.3 These examples suggest that combining the setting of a tournament and a narrative centred around themes of gender fluidity and subversion creates a story that seems fully in line with both medieval literature and actual events.

As the subtitle of the game – A Modern Medieval Folk-Tale – suggests, I wanted to tell its players a story inspired by the rich, colourful and occasionally outright weird tapestry of late medieval history and literature, but also one with contemporary sensibilities about gender, queer relationships, and subaltern agency. Throughout the development process I have found that the sources provide a wealth of materials for these kinds of stories, and that if game designers are willing to engage constructively with the complexities of the past, historical games can be so much more than just the same old tired male-protagonist power fantasies we have seen too many times already.

Andreas Kjeldsen is a game developer, translator and writer from Copenhagen, Denmark. Coming from an academic background with graduate degrees in History (U. of Copenhagen) and Medieval History (U. of York) and later turning to a career in translation and subtitling, he is now trying to survive the absurdities of modern late-stage capitalism and growing authoritarianism by telling digital stories about worlds that don’t exist. Upcoming releases from his studio Stark Raving Sane Games include The Knight & the Maiden: A Modern Medieval Folk-Tale, a narrative adventure game inspired by the Late Middle Ages, and Adventurer Lords: Fallen Lands, a blend of fantasy roleplaying game and political management sim. He lives outside Copenhagen together with two imaginary cats and the restless ghosts of the past. You can follow him on Bluesky or subscribe to his newsletter to stay updated about future game releases.

- Katie Vernon, ‘Queer-ying Gendered Representation of Combat Professions in Medievalist Video Games’, Historical Games Network (accessed July 23 2025). ↩︎

- James Baillie, ‘Between Imagined Worlds: Reinterpreting Medievalisms in an RPG’, Historical Games Network, (accessed July 23 2025) ↩︎

- Vernon, ‘Queer-ying Gendered Representation of Combat Professions in Medievalist Video Games’. ↩︎