“Prior to photography, places did not travel well” (Urry and Larsen 2011, 166). If the advent of photography heralded the increased conceptual portability of places, what does the representation of those places in video games mean? What are the ethical implications of engaging with video games as a form of digital tourism, especially when the ‘tourist gaze’ is so intertwined with colonial fantasy? Moreover, how should we consider sites of trauma or suffering in video games as digital tourism experiences?

This piece doesn’t seek to pose definitive answers to these questions, but to provoke discussion and introspection about our motivations as academics who study video games.

It seems fitting, then, for me to introduce myself: since 2016 I’ve been conducting research at the intersection of archaeology and video games (aka ‘archaeogaming’). In 2018, I published a book chapter arguing that certain video games could be considered dark tourism experiences (chapter 14 in Champion 2018). Defining the remit of dark tourism can feel like trying to pin a shadow to a corkboard, but very broadly it is the deliberate visitation of sites marketed as tourist destinations which are associated with death and disaster.

Dark tourists have been criticized as voyeuristic, the dark tourism industry exploitative, and the academics that study both as benefitting from their own privilege of (often) being scholars from the Global North (Korstanje 2017). I want to explore the limitations and ethical implications of considering video games as dark tourism experiences through one notable case study: Umurangi Generation.

In the first section below, I will explore how Umurangi could be considered a dark tourist experience, and in the second I will extend that argument to examine how the game satirises the tourist gaze.

Gamer culture as dark heritage

Umurangi Generation is not necessarily an obvious choice to discuss digital dark tourism. It is a first-person photography game set in near-future Tauranga, Aotearoa. It was primarily made by Māori developer Naphtali Faulkner (also known as Veselekov) who currently lives in Australia. You play as a courier tasked with taking photo bounties to survive even as a kaiju attacks your UN-occupied city. If you think that a game like Umurangi Generation cannot be considered as a dark tourist experience on the grounds that it is science fiction, rather than a virtual recreation of a non-fictional heritage site, I would disagree with you on several counts.

Firstly, Umurangi Generation can be conceived as a game about recording our future heritage. In an interview with The Indie Game Magazine Faulkner explained that “the concept of the game’s story and themes came from my experience with the bush fires that happened in Australia and the government’s shit house job at not only reacting to them but ignoring the issue of climate change for years” (Sims 2020). If the kaiju is read as a metaphor for the climate crisis, then Umurangi is like an artefact from one very feasible future.

Furthermore, the game may be science fiction, but it is very much informed by Māori culture surviving in spite of colonialism. As Dan Taipua puts it:

“Every single artistic vision of a Māori future or a future for Māori is an act of resistance against extinction… We who had been literally, mathematically decimated by epidemics in the past; we who invented and practised rāhui over a thousand years. In real life, in everyday life, there are forces around us always that conspire to destroy history itself, making every gesture towards a future, towards continuity of existence, a meaningful one”.

Umurangi Generation is art that resists colonial logic simply by existing. It also refers to what could be considered the dark heritage of the British colonisation of New Zealand, especially as the game includes references to historical sites of Māori resistance (Jardine 2021).

There is another aspect of Umurangi that could be seen as a digital dark tourism experience: its parody of ‘gamer’ culture. The DLC includes the level ‘Gamer’s Palace,’ a seedy bar at the end of the world. In my mind it is a museum of toxic gamer-bro consumerism. One section lines up a series of spoof game posters and invites you to take your shot: there’s “Angry Manchild VR Reviews,” “Apolitical Freedom Revolution Power Fantasy,” and “Deth” which promises “No ‘Artistic Vision’” and “No Pronouns.” Meanwhile, there are women in bunny ears reminiscent of E3 booth babes, and holographic “Insta-Waifus” that never tire of dancing. ‘Gamer’s Palace’ may be very on the nose in its critique of gamer culture, but that’s precisely why it is such an affective digital dark tourism experience. This unflinching portrayal of bigotry in the games industry is essential, as we continue to hear about allegations of sexual abuse and harassment within it (Hollister 2021).

The tourist as first-person shooter

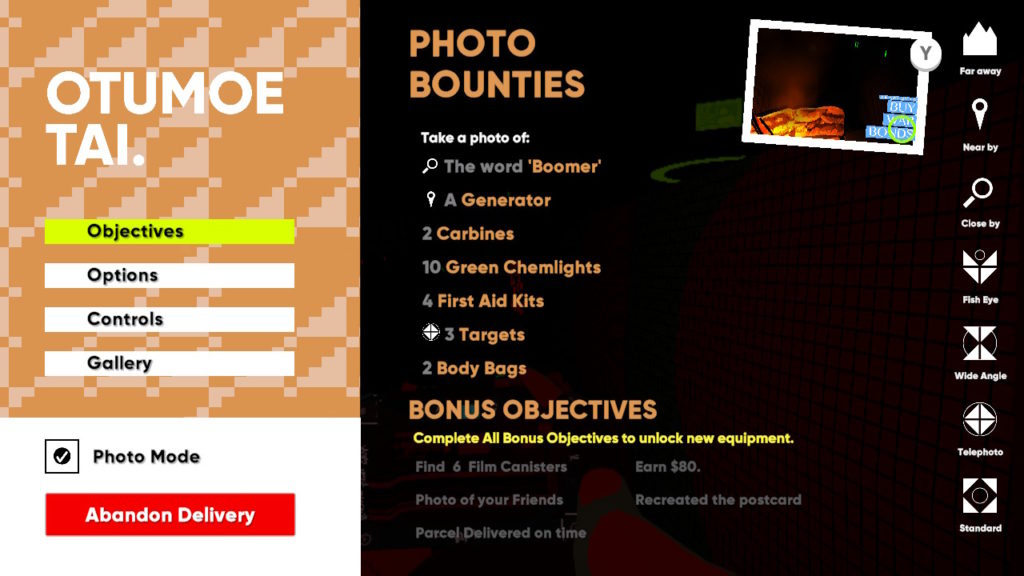

While you could argue that Umurangi Generation is a dark tourism experience in some respects, I think there is a much stronger argument to make for the game being a critique of dark tourism. The game does this in several ways through the photography mechanic, which is literally a framing device for the vibrant low-poly world that Faulkner has created. In each level, you have several mandatory photo bounties, along with some optional ones. One of these is the task of recreating a postcard image. The postcard is one manifestation of what Urry and Larsen call the ‘tourist gaze:’

“Photographs do not only make places visible, perform-able and memorable, places are also sculptured materially as simulations of idealized photographs as ‘postcard places’” (Urry and Larsen 2011, 174).

The postcard bounties are arguably the most prescriptive tasks in Umurangi. As the game progresses, their challenge becomes not just one of recreation, but of countenancing the jarring nature of that recreation in the context of levels such as Otumoe Tai which becomes a war zone. The absurdity of creating ‘postcard places’ in this apocalyptic context underscores the privilege of the dark tourist gaze, as the protagonist must scramble to make a living from selling these images to be (presumably) consumed by an audience distanced from the conflict.

Umurangi is not seeking to provide a curated experience of Māori heritage palatable to the tourist gaze either. As Faulkner explained in an interview:

“Oftentimes, when we see Māori portrayed in games we see this nomadic warrior. People just put moku on a character, and then they’re the warrior character. Or we’ll see Māori [representation] but it’s ‘edutainment’” (Jardine 2021).

One of the objectives in The Depths required me to take a photograph of a taiaha. I didn’t know what that was, but I do now because I Googled it. This game is not interested in explaining itself to you. Instead, it provides a space for your own meaning-making through photography. It is not interested in teaching white Westerners like me about Māori culture, it invites me to educate myself. For these reasons, Umurangi Generation is a deeply generous game.

Umurangi satirises the photography as tourist gaze but celebrates the camera as a tool for self-expression. Faulkner has a background in respectful design, developed by the Aboriginal Australian designer Dr Norm Sheehan. As Faulkner puts it:

“it says agency is with a community, not the designer who comes in. For this game, the players (the community) decide how they want to take photos and what is a good photo, not the game (the design)” (Sims 2020).

In Sheehan’s article ‘Indigenous Knowledge and Respectful Design: An Evidence-Based Approach,’ he discusses an exercise in which students created an emergent narrative through the use of visual dialogue cards that they rearranged as a group (Sheehan 2011). Umurangi encourages you to create your own emergent narrative through digital photography. Writing about alternate history games as dark tourism, Caleb Andrew Milligan considers the “active rewriting when we perform the role of media archaeologist in these almost histories” (Milligan 2018, 278) I think Umurangi goes beyond this, as Faulkner considers players:

“Taking their own photos ties them to the world; they have taken an artefact of the world, which is something they will look at and remember how they felt in that space” (Couture 2021).

In Umurangi you are not just rewriting history, you are reconfiguring what history itself can be.

Change the lens

Umurangi Generation is less about being a tourist (dark or otherwise) than it is satire of the tourist performance as death ritual at the end of the world. This isn’t to say that viewing it through the lens (pun intended) of dark tourism isn’t without merit, just that Umurangi eludes being typologised by the tourist gaze. To be a dark tourist is to position yourself at a distance, consuming through observation. This is a key limitation of dark tourism as an academic construct – it would be unethical to centre it or myself in this discussion, or pose that dark tourism studies are the authority on sites of trauma and suffering. Ultimately, it is not my place as a white British scholar to define what Umurangi Generation can be. What I’ve learnt from playing the game, and researching respectful design, is that my practice as a digital archaeologist benefits from creatively engaging with the medium. Furthermore, the history of Umurangi Generation cannot be written by one person, and its archaeology belongs to the community of players. Maybe a hundred years from now some of the photographs from this game will endure – what stories will they tell?

All images captured by Florence Smith Nicholls, from Umurangi Generation (Origame Digital/Playism).

Florence Smith Nicholls is an archaeologist, freelance writer and narrative designer. Since 2016 they have conducted research in the field of archaeogaming. They are an incoming PhD student on the IGGI programme at Queen Mary University of London, working on procedurally generated archaeology games. You can follow them on Twitter (@florencesn).

One reply on “Picture Imperfect: Photography, Dark Tourism and Video Games”

[…] Picture Imperfect: Photography, Dark Tourism and Video Games | Historical Games Network Florence Smith Nicholls unpacks the concept of Dark Tourism and studies how Umurangi Generation makes some use of but predominantly critiques the practice and reveals its limits. […]

[…] Florence Smith Nicholls: Picture Imperfect: Photography, Dark Tourism and Video Games […]