Within games is there not a huge gap in the creation, availability, and discovery of non-western perspectives? What space do game-makers have to challenge the norms of working within a discourse of global capital, of industrial histories entwined with capital and power? Where is the gameplay that does not simply revolve around victory sought through conflict, dominance, and resource exploitation? Can game-makers offer access to a playable past which is not simply neo-colonial, or characterised by erasure?

These were prompts and questions raised by the original call for papers on this topic. What follows is a state-of-the-field response that aims to overview a specific category of analog games: what we might broadly call historical simulation games, or, perhaps, history games. These are games that make overt attempts to model what their designers determine to be one aspect, or more, of historical reality. Here, I suggest, we have good reason to be optimistic about recent design developments, and permit us some means of answering at least some of those questions above in a positive light.

Agency and Reconceptualising Victory

Since their inception, wargames have given us an avenue to asymmetric gameplay – modelling reality where different sides have different military strengths and different military objectives. As analog wargames have developed into a hobby, waxed, waned, and waxed again in popularity, and as they have combined with mechanics from other genres, they have given us new forms.

From design roots in asymmetry, combining with the often neglected topic of irregular warfare, together with Euro-game derived mechanics and components, we saw GMT Games publish (former CIA analyst) Volko Ruhnke’s Labyrinth: The War on Terror 2001- (2010) about the global war between the USA (and allies) and terrorist organizations. Shortly after this, GMT began to publish Ruhnke’s similarly derived COIN (COunter INsurgency) designs. This (still ongoing) series has given us games on Afghanistan (A Distant Plain, 2013), Vietnam (Fire in the Lake, 2014), Caesar’s Gallic Wars (Falling Sky: The Gallic Revolt Against Caesar, 2016), and the Algerian War for Independence (Colonial Twilight: The French-Algerian War 1954-1962, 2017) – amongst many others.*

In two key ways, these games have been significant in opening a path to anti-colonial narratives. Firstly, these games give agency to the colonized, or the would-be colonized, or the anti-western or imperial faction. This alone is not groundbreaking – miniature wargamers from the 1950s onwards had done as much as they re-fought colonial wars on tabletops. But, crucially, the second thing these games brought – in conjunction with that agency – was a conceptual expansion beyond mere combat. They gave irregular forces, the colonized or would-be colonized, appropriately themed and scaled asymmetric routes to victory which re-contextualized what is meant by dominance, and redefined what military victory is worth within a political context.

Irregular forces, then, are not tasked with defeating regular forces in battle, something they will most often fail at. Instead, they are tasked with defeating regular forces in more protracted sub-conflicts (such as regional popularity, or with regards to the efficiency of intelligence networks) which are the true measure of winning in irregular warfare. This anti-colonial narrative is even clearer when one considers some of the more recent titles in this COIN series: Gandhi: The Decolonization of British India 1917-1947 (2019), and The British Way: Counterinsurgency at the End of Empire (forthcoming).

We can look elsewhere too for anti-colonial narratives in history games – with games like 1979: Revolution in Iran (forthcoming) where players attempt to either retain or depose the Shah. Even more tellingly we see the anti-colonial narrative in a game like Pax Pamir second edition (2019 – first edition, 2015), where the game is set during the ‘Great Game’ of imperial British and Russian rivalry in Afghanistan, but players play as Afghan leaders (the historical notes of the first edition give us something more like an apology for imperialism).

Zenobia Awards

Out of these recent developments, we are now seeing games not necessarily concerned with warfare at all. Some game are adopting design methodologies and certain mechanics from this tradition to explore other historical topics, some of which are further developments in anti-colonialism, or might even be considered examples of post-colonialism.

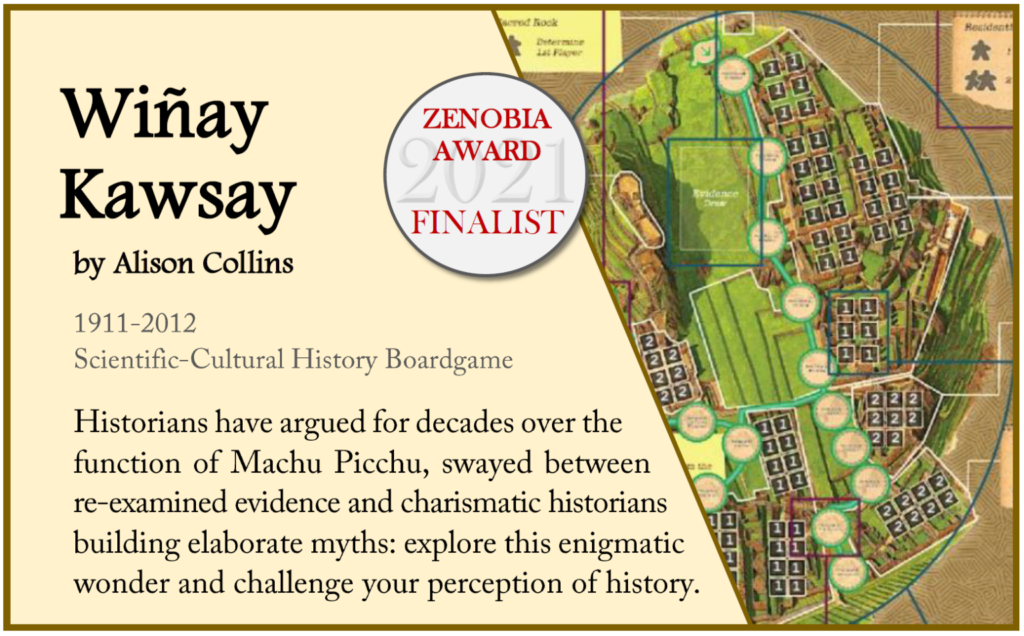

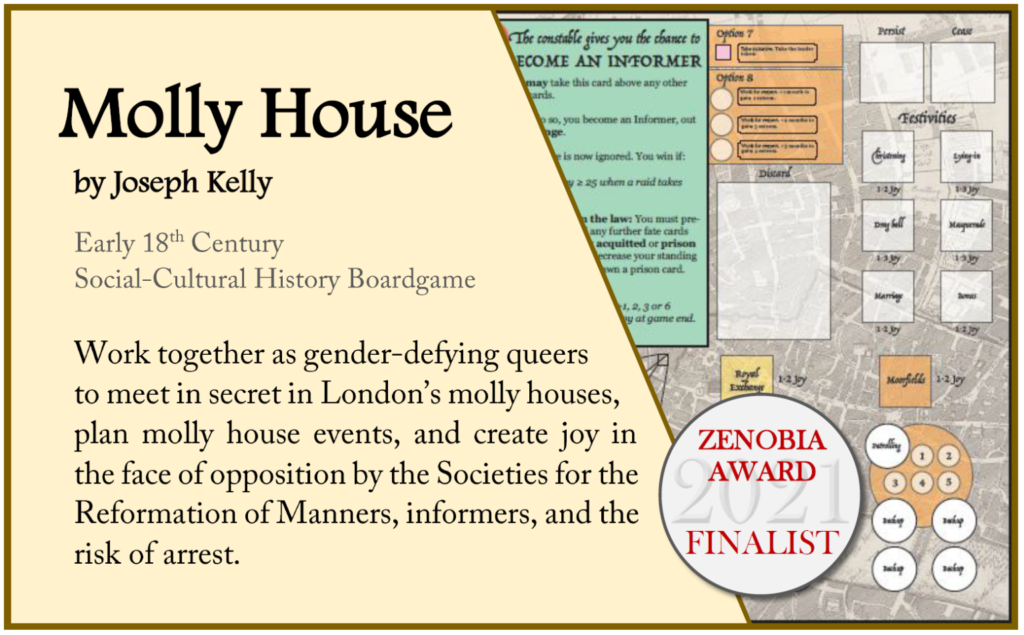

We get some sense of these developments if we look at the recently (August 15, 2021) announced list of Zenobia Awards finalists. The Zenobia Awards is an initiative in its first year seeking to encourage designers from marginalized groups (women, people of colour, LGBTQ+) to design board games/ tabletop games attempting to tackle some historical topic – not necessarily warfare. It seems no coincidence that Volko Ruhnke is one of the key voices behind this initiative. The eight finalists are:

● From Darkness to Light – set during Indonesia’s struggle for independence from the late 1800s to early 1900s, players manage a school attempting to graduate women in preparation for independence. (Designer: Sherria Ayuandini.)

● Liberation Haiti – set during the 1789-1794, play as enslaved Africans and escape slaves to eject the colonial French forces. (Designer: Damon Stone.)

● Molly House – set in eighteenth century London, play as gender-defying queers meeting in secret, risking arrest, as you attempt to collaborate and spread joy. (Designer: Joseph Kelly.)

● Orange Shall Overcome – set during the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands, work together to defy the occupying forces. (Designer: Marcel Köhler.)

● The Season – set in Regency England, manage the activities and reputation of your household’s young ladies. (Designer: Lauren Ino.)

● The Tyranny of Blood – set during the rise and fall of British colonialism in India; attempt to manage your caste’s fortunes from 1700-1947. (Designer: Akar Bharadvaj)

● Wiñay Kawsay – play as historians arguing over the evidence for different interpretations of Machu Picchu. (Designer: Alison Collins.)

● Winter Rabbit – set during a pre-Columbian world, manage your economic system based on reciprocity and community, but beware the trickster rabbit of Cherokee lore. (Designer: Will Thompson.)

Here, then, we can see exciting and ambitious attempts to take us into new pasts, freshly reimagined, with different perspectives, that give some sense of what may be possible in the future. The (often combined) traditions these games are borrowing from in terms of mechanics are clearly demonstrating considerable flexibility with regards to subject matter. Now it is also clear there are voices who have new stories to tell with these tools.

This space in the gaming universe is not without its issues – as the 2019 controversy over GMT’s Scramble for Africa demonstrates. Here was a game that appeared to evoke notions of the exotic unknowable savagery of the dark continent in its box cover art, and appeared to be using the theme of colonialism to wrap a game about Europeans exploiting indigenous resources. Such was the controversy that GMT pulled the game from publication – which was a controversy of its own too, as counter claims of censorship and erasure abounded.

This gaming space as a whole is also riven with potentially deep political divisions. The audience for wargames traditionally brings with it an enthusiasm for military history, which sometimes means abundant intellectual curiosity that veers towards progressivism, and at other times this enthusiasm for military history veers towards conservatism, and each of these perspectives is sometimes amped by past or present military service.

However, the Zenobia Awards perhaps show us that there is far more to history games than regular warfare, far more than warfare of any kind, far more than colonialism and imperial expansion, more too than western perspectives. In fact we now have the design tools to make so much more of history a playable space. Even before Zenobia we had games such as Freedom: The Underground Railroad (2012), which tasked players with being abolitionsists, or The Vote: Suffrage and Suppression in America (2020), and Votes for Women (forthcoming), both of which look at the history of women’s suffrage in the USA, or we had games such as 1960: The Making of the President (2007) about the Kennedy Nixon election, or This Guilty Land: The Policies of Slavery in America (2018). If we can harness this momentum we have good reason to be optimistic about the future of the playable past in analog games.

* Some of the games in this series have been designed, or co-designed by designers other than Volko.

Maurice Suckling has worked on over 50 video games, including Driver (1999), Borderlands: The Presequel (2014, and Civilization VI (2016). He also designs board games, including Freeman’s Farm: 1777 (2019), and Chancellorsville: 1863 (2020). He is an assistant professor in the Games Simulation Arts and Sciences program at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, New York.

Disclosure statement: Maurice Suckling is a mentor giving voluntary support to the Zenobia Awards.