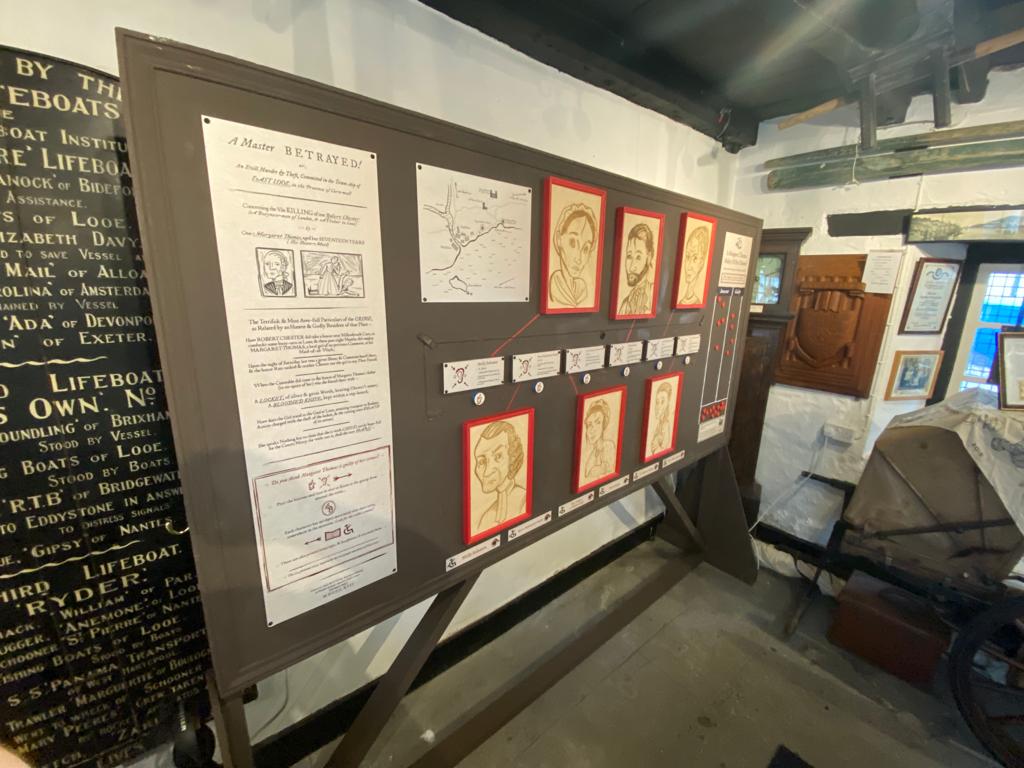

A Master Betrayed! is a set of physical and digital interactive narrative works, connected with the East Looe Old Gaol Museum in Cornwall, UK. This volunteer-led museum, occupying the medieval magistrate’s court building at the centre of this small fishing port, tells of the town’s civic, social and economic history through the stories of the people that once lived there. You can visit the physical exhibit at the East Looe Old Gaol Museum.

The project was originally devised as a way to provide a space in the museum that was explicitly for Looe’s residents, rather than tourists. It would explore their chosen themes, stories and concerns, linking Looe’s past and present: overtourism, rural poverty, deindustrialisation, regional identity and the threat of rich ‘incomers’ have always been part of the Cornish story (Gornik, 2021). Finding only scattered materials to support such narratives in the museum’s archives, we instead decided to tell a fictional story set in the town. While informed by the archival materials, it would also turn for inspiration to the local landscape, the anecdotes (and complaints) of Looe’s residents and the growing interest in the intangible, subjective and speculative in heritage interpretation (Ludwig and Wang, 2020).

Set in 1763, the story centres on a fictional murder which the visitor – whether physical or digital – is tasked with solving. Robert Chester, a rich Londoner who has been visiting Looe on business, has disappeared from his lodgings. There is no body, but the house is in disarray and witnesses report hearing screams.

The main suspect is his maid: a young local girl called Margaret Thomas who was found at her parent’s home, with a silver locket belonging to Chester and a bloody knife hidden under her bed. Arrested and held in the magistrate’s court (the future museum building), she faces the death penalty. She claims that she is pregnant (perhaps, as many sneer, to delay her sentence [Bitomsky, 2015]), but will say nothing else in her defence.

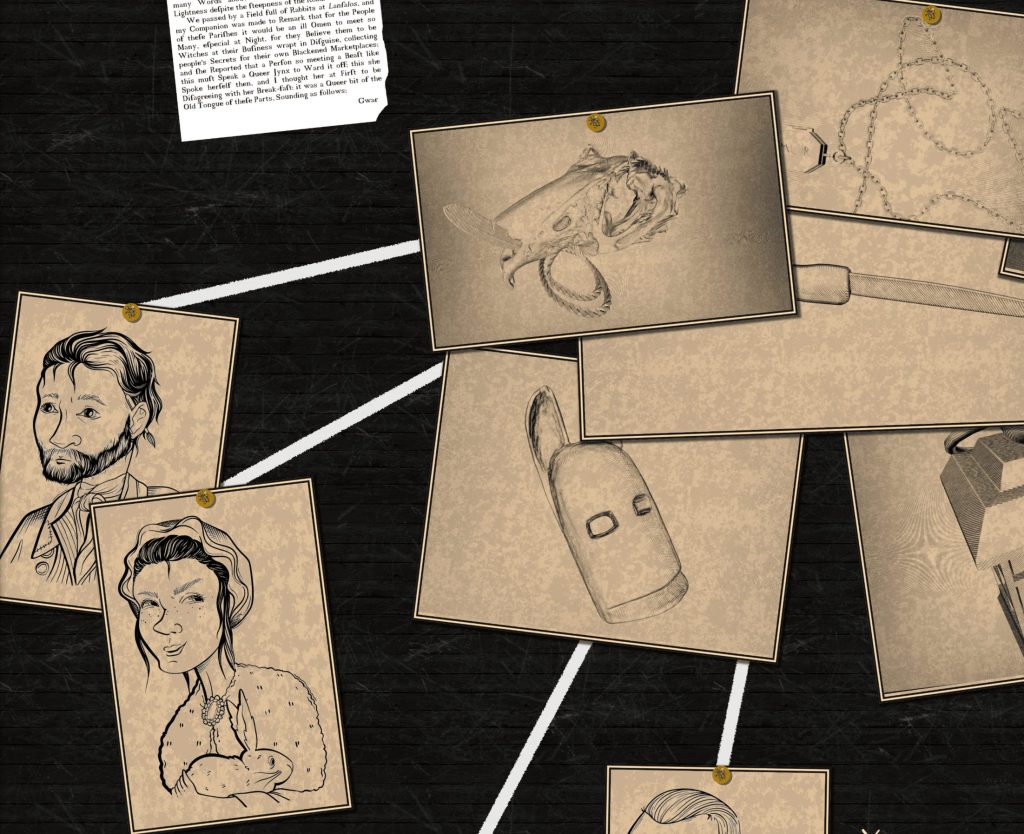

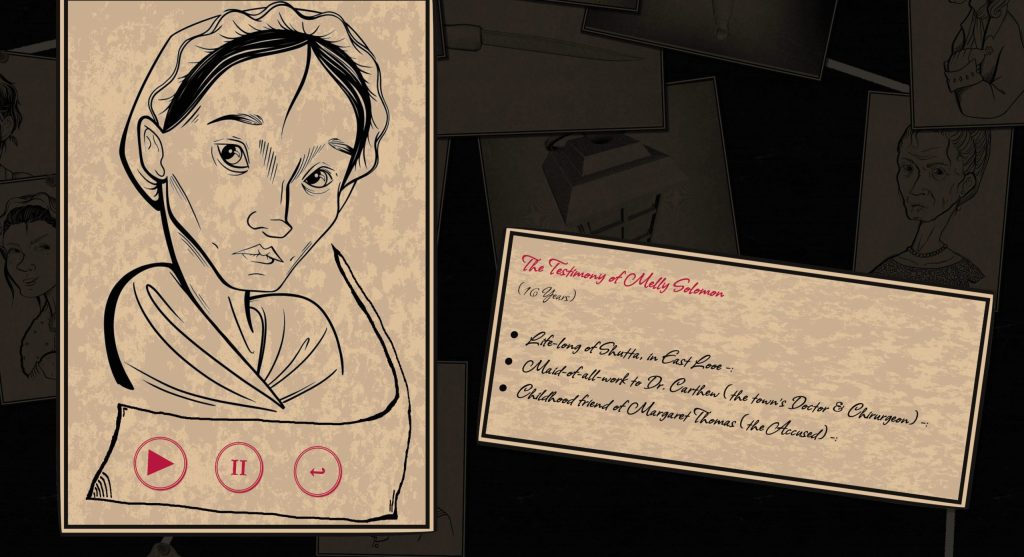

The visitor begins to examine the evidence laid before them: sensationalist broadsides drooling over the gory details of Thomas’ alleged crime; letters; maps; scribbled interrogation notes; physical objects (and their digitised, 3D counterparts) which can be manipulated and studied for clues. Most importantly, the visitor listens to six witness testimonies from local people connected to the town and Margaret herself. Studying, manipulating and comparing these sources, the visitor must then make a decision: is Margaret Thomas guilty? And if not her, then who?

While this common ‘epistemic’ conceit provides both the narrative and mechanical scaffolding for the interactive experience (Ryan, 2001), the process of investigation also reveals much about Cornish society at the time – and, by design, its similarities with Cornish society today. Rather than simple sources of information about the crime, the evidence presented shows the complexities of the world in which Margaret and the other characters lived.

Of all these complexities, the role of women in 18th century society is central: to the crime itself, the response to that crime, and what is revealed of this small, close-knit community in the wake of its investigation.

Margaret Thomas is, of course, the most obvious vector: a woman whose public condemnation and impotent silence licenses others in her community (and beyond it) to censure and mischaracterise her in line with the hierarchical and patriarchal society in which she lives. While the visitor’s own society is (they may feel) far removed from early modern sensibilities, there is a discomfiting familiarity in the way Margaret’s guilt is heightened by her unwomanly confidence, her interest in material goods above her station, and her sexual intemperance. This publicity also reveals, by proxy, the gendered lives of other women in Looe, connected to Margaret. Her best friend Melly Solomon has her own story to tell: of abuse by her employer, and a repressed homosexuality that has little outlet other than steadfast and tortured loyalty to her friend.

One witness, Kate Renshaw, presents another view of womanhood at this time: that of the relative financial and social independence of the ‘pellar’, or ‘cunning woman’. These practitioners of ‘low’ or ‘popular’ magic represented one of the only viable routes to independence amongst single women at the time (Davies, 2007). Indeed, the local folk beliefs upon which Renshaw draws suffuse the investigative work of the visitor, and are often framed as a means for women to pursue agency in a world that afford them little. These include Melly’s carved idols attempting to magically influence her doomed friend into loving her, the knowing parlour tricks that Kate plays on unsuspecting tourists, and the rumours of charms and potions designed to provide women like Margaret with some form of reproductive autonomy (Davies, 2007).

When the visitor comes to judge Margaret Thomas – weighing evidence and counter-evidence, rumour and claim – they also stand in judgement of these other women. All are fictional, but representative of lived experiences and social structures that have changed, but not disappeared, with time. Deciding who killed Robert Chester is, indeed, more of a decision about the character of Margaret Thomas herself: is she a brutish and materialistic harpy? A manipulative harlot? A foolish girl, manipulated in her turn and condemned to a life of single motherhood?

When the truth is revealed, the answer may surprise the visitor here in the twenty-first century: an answer which tries to honour the subjective, intangible and polyphonic voice to which historical works (including games) are increasingly lending to the past.

Links for A Master Betrayed!

Web Version (Laptop/Desktop, Firefox or Chrome).

Downloadable Version (Windows, Mac, Linux).

Rob Sherman is a digital artist, interactive narrative designer and lecturer in Interactive Storytelling at Exeter University.

Works Cited

Bitomsky, Jane ‘Pleading the Belly: Pregnancy and crime in seventeenth-century England’. University of Queensland: ANZAMEMS, July 2015.

Davies, Owen Popular Magic: Cunning-folk in English History. London: Bloomsbury, 2007

Gornik, Vivian B. ‘4 Uses of the Past: Heritage, Tourism and the Challenges of (Re)Producing Contemporary National Identities in England’. In Tourism and Brexit: Travel, Borders and Identity, edited by Hazel Andrews, 48–65. Channel View Publications, 2021.

Ludwig, Carol, and Yi-Wen Wang. ‘5 Contemporary Fabrication of Pasts and the Creation of New Identities?: Open-Air Museums and Historical Theme Parks in the UK and China’. In The Heritage Turn in China: The Reinvention, Dissemination and Consumption of Heritage, edited by Carol Ludwig, Yi-Wen Wang, and Linda Walton, 131–68. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.

Ryan, Marie Laure. ‘Interactive Narrative, Plot Types and Interpersonal Relations’. In Interactive Storytelling, edited by U Spierling and Nicholas Szilas, Springer, 2008.