The medieval period offers an opportunity to think about gender through its popular stories and use of arms and armour to construct the bodily identity of those involved in combat roles. This blog post examines how these themes are brought to life through medievalism and fantasy in video games.

The blog aims to introduce three frameworks for thinking about gender representation and arms/armour of female characters in medievalist games, exploring themes like the fluidity of identity, subversive power, and storytelling. It is based on, and developed from elements of a workshop I ran at the Royal Armouries on the 1st of March 2025: ‘Queer Representation in Arms and Armour of Pop Culture: Medieval to Modern.’ The first two sections use the theoretical frameworks of female masculinity and the term ‘lesbian-like’ to explore female warriors in fantasy games. The final section uses queer body theory to consider the ways in which the body can be constructed through arms and armour.

What is Medievalism and Queer Medievalism?

Medievalism is the depiction and drawing on ideas of the medieval period in modern works, including medieval-themed fantasy. A branch of this is queer medievalism, in which:

potential queerness arises when acts of the present redefine the cultural meaning of genders and sexualities in the past, through a transtemporal and oscillating vision between yesterday and today. It also resides in the power of the past to destabilise modern conceptions of gendered and erotic identities.1

This quote might be simplified to suggest that modern depictions of the medieval past provide a space to explore ideas of gender and sexuality. The past opens this space to consider modern constructs of gender and sexuality because in the medieval period, these concepts may not have been thought of in the same way. Therefore, looking to the past can provide opportunities to question modern identities, whilst modern theories can also be used as frameworks to consider past identities.

As the original owners of many weapons in our museum collections are not known, an element of imagination is needed to think about who might have owned and used them. The Cheapside Poleaxe, excavated in Cheapside, London, is an example which I often use when discussing how people constructed and showcased their social class and profession through weapons. Cheapside was a place where lots of crafts and mercantile households were based, but this hefty weapon might also be used to think about gender and profession. Both men and women worked in craft households, for example, labouring as armourers, and so these medieval items are not just present in the households and workshops of men, but also women. As such, using the medieval past to think about gender and profession provides the potential to consider gender in an intersectional way.

Female Masculinity and Warrior Women

A framework for gender that might be applied to many medievalist video games is female masculinity, coined by Jack Halberstam.2 This term is used for the qualities and categorisation of masculinity that might be applied to women, not just men. A clear example of an identity connected to this is that of the Butch Lesbian. Halberstam examines female masculinity throughout the past. Scholars like Rachel Delman have gone even further back in time to consider female masculinity for medieval women in positions of lordship, owning and overseeing land they had responsibility for, or during activities like hunting.3 My own research explores how this term can be used to think about women in charge of military defence and using arms and armour. By using the term female masculinity, it is possible to be more flexible with expressions of gender.

The medieval depiction of the Amazons in popular stories might provide an example that can be imaginatively compared to female masculinity in video games. The Amazons were a society of only women who lived in the distant past. While some perceived these warrior women as threatening, they were often used in women’s circles as positive depictions of femininity.4 The Amazons’ martial abilities, armour and weapons (usually swords and lances) were a strong part of their identity.

In an early fifteenth-century manuscript of the romance Laud Troy, Penthesilea (the Queen of the Amazons) and her female warriors are described with terms possibly more expected of the traditional male knight in action-packed adventure stories.5 She has martial qualities like bravery, sternness, hardiness, boldness, keenness, might, and she is described in the same terms as Hercules in the poem, like a fierce polecat. However, Penthesilea and her maidens are here not gendered as male, but instead defined by their warrior profession. As such, the Amazons might be considered to have aspects of female masculinity in their depiction, especially in how they were often dressed half in armour and half in female clothing.

The social construction of warrior women through female masculinity is insightful when considering the many fighting women in video games. In Baldur’s Gate 3, Karlach, while in some ways feminine, is also a tiefling barbarian who exhibits elements of female masculinity. She is a burly woman who can use big two-handed weapons, like great swords, maces, and halberds. Similarly, Lae’zel is a strong warrior, part of the fighter class with sword proficiency. However, she is characterised very differently from Karlach, with a much stricter, harsher form of military masculinity which is linked to her Githyanki culture.

Here, the medievalism of Baldur’s Gate 3 provides a lens to explore female masculinity. It provides the tools (weapons) and combat-oriented situations that are associated with masculinity to allow a player to explore a character’s personal storyline and their in-depth characterisation. Like the Amazons, discussed above, these video game warrior women are not sacrificing their status as women to be masculine, but instead, female masculinity allows for a more complex characterisation of individual gendered identity. These examples illustrate a spectrum of female masculinity and how it is enacted.

The RPG genre has increasingly allowed for this flexibility with its customisable characters. For instance, the Elder Scrolls series allows players to live their fully-fledged female Orc or Nord barbarian dreams. The mythology of such games inspires other forms of entertainment. The main character of the cosy fantasy book Legends and Lattes (2022), heavily inspired by Table-Top Role-Playing Game Dungeons and Dragons, is the Orc warrior, Viv. In each of these examples, the women’s characterisation stems from their professional identities as warriors, dressed in armour, wielding massive weapons, and often battle-scarred and muscular. This professional identity, using weapons as tools of the trade, intersects with an expression of queered gender.

Lesbian-like and Lesbian as an Adjective

Another valuable way of thinking about queer gender in medievalism and video games is through the term “lesbian-like,” or the use of lesbian as an adjective. Judith Bennett notes how difficult it can be to find historical examples of people along the queer spectrum.6 Bennett proposes instead the term “lesbian-like” as a theory which affords opportunities to examine histories of women whose lives might have queer opportunities, such as living in female only communities or cross-dressing.7 The term is designed to be broad enough to prompt researchers to think about historical women and their behaviour through a non-heteronormative lens.

Similarly, as Emma Nuding discusses, the term lesbian can be used not just as a noun but as an adjective and as a way of thinking about queer identities in the past.8 Nuding explores how medievalism and ideas of the medieval period can offer spaces to play with gender and queer relationships, especially through opportunities to cross-dress as knights or pages, where the damsel in distress might be with a knight who is played by a woman. These can be spaces to subvert conservative ideas of the medieval past, where the chivalric past is reimagined through queer desire.

The forthcoming The Witcher 4, where Ciri will be the protagonist, will hopefully provide opportunities for exploring queer desire and lesbian-like figures. The books and games show her to be bisexual. Playing as Ciri in The Witcher 3 develops her lesbian-like characterisation. The sauna scene reveals her thigh tattoo of a rose, emblematic of her abusive lesbian relationship with Mistle. The sauna dialogue progresses this characterisation by allowing the player to choose whether Ciri says she prefers women.

Furthermore, throughout her life, Ciri takes up different roles and their associated dress, including princess, bandit and witcher. Her role as a witcher is part of a heavily masculinised profession in both the books and the games, as the mutant trials on girls and boys led to only boys surviving. Previously, the only exception to the male rule was the 2001 tabletop RPG, which has a female witcher; however, Sapkowski has gone on record recently to say that witchers could be of any gender.9 Ciri is included in this male-dominated field; she is called a ‘little witcher girl’ in the books as she is trained as a witcher, with The Witcher 3‘s journal entry recounting how Geralt brings Ciri to Kaer Morhen.10 He ‘[f]ollow[s] [an] age-old witcher tradition’, to train her ‘in the ways of the professional monster slayer’. Similarly, in the books, at Kaer Morhen, Ciri is given herbs and mushrooms which inadvertently interact with her hormonal development, making her more androgynous. As such, Ciri occupies multiple roles, with varied gendered expectations.

There are a few exceptions, such as Queen Meve, Pretty Kitty and Rayla, but for the most part, in TheWitcher universe, fighting professions are undertaken by men. Being a witcher is extremely dangerous, with Geralt’s assertion that “no witcher had ever died in his own bed.”11 The use of Ciri as a protagonist will provide an additional perspective on how the game explores its gender roles. The player sees short insights into this gendered world through the playable moments where Ciri enjoys the spoils of hunting a boar with the Bloody Baron’s men, races horses with the Baron, and kills a basilisk. All these activities, even when undertaken by women, are often associated with masculinity in both medieval contexts and representations in medievalism. Seeing Ciri as the protagonist will be particularly interesting, too, for developing contemporary cultural narratives of medieval female warriors, as we know that women were involved in conflict throughout the medieval period.

Queer Body Theory: Armour as Constructing the Body and Gender

Queer body theory is a useful framework for considering how armour shapes the body. This theory interrogates how cultures imagine and construct gendered bodies. What is a normative body? Who has constructed and enforced this idea? How might we go about changing what this means? How can we imagine a future where we might disrupt these norms? These questions can be explored through Judith Butler’s assertion that a body is not a static object but rather, is formed by how one uses it.12

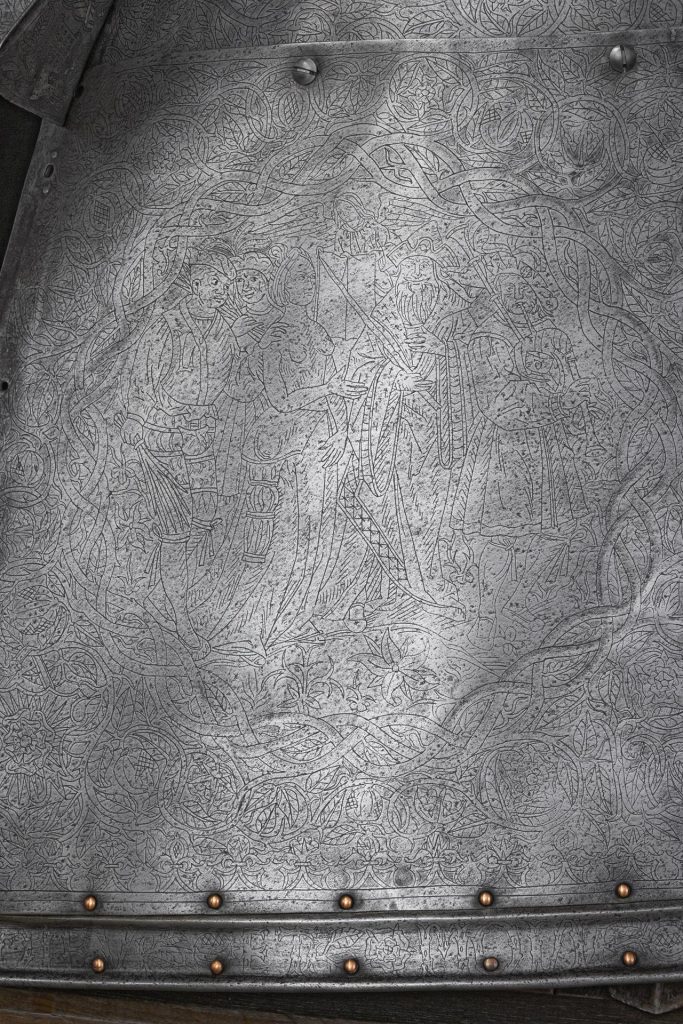

Armour itself makes for a great way of thinking about how gendered bodies are constructed because it shapes the body and sometimes even anonymises the wearer. It also symbolises power and can be a high-fashion item. While from the late-medieval period onwards, suits of armour were close-fitting, and so in some ways provided a snapshot of the wearer’s body, they were also able to emphasise or build the body in interesting ways. Some examples are those such as Henry VIII’s tournament armour and the Roman muscle cuirass, which emphasises an image of male virility and strength. Not only were bodies covered with gendering armour, but armour could be covered with gendered bodies; as in the example of Henry VIII’s horse armour, which shows a naked figure from the waist up, Saint Barbara. This armour celebrates Henry and Katherine’s union with combined imagery of H & K, the rose and pomegranate (personal emblems), and St George and St Barbara as national saints. Here, an extremely masculine figure is also drawing on elements of female and feminine imagery and power.

I like to use the above examples in comparison to the much-vilified boob plate. This type of armour, familiar to many who play medievalist video games is often, of course, hugely problematic and frustrating. This armour can be incredibly sexualised and the only armour available for female characters; the stereotype of the chainmail bikini is well satirised in the Viva La Dirt League videos. This sexualised armour can be impractical and uncomfortable, with parts of the body dangerously revealed. Additionally, it might be shaped in impractical ways that direct blows further towards the wearer, rather than away. For instance, Lae’zel in Baldur’s Gate 3, not only has large gaps between her plate armour, meaning areas would be unprotected, but also there is no underlayer beneath the plates, where usually there would be clothes, padding and even chainmail. Similar criticisms might equally be applied to high heels, with Ciri’s heels being too tall to be compared to early riding heels.

However, there might be potential to interpret this in future, in more interesting ways, when compared to bras from high fashion, as in the example of Madonna’s Jean Paul Gaultier cone bra, which was used as a statement of female power. This provides a mirror image of male armour, which highlights ideas of masculinity with the example of the muscle breast plate, or with weapons like the wearing of the ballock dagger in front of the crotch. A more obvious example of this would be the phallic codpiece, especially those worn by Henry VIII alongside his characteristic form-fitting armour, which shaped and emphasised a masculinised body, but which did not always meet regulations at tournaments.13 This shaping of an armoured form could be interesting to consider from the perspective of performing gender by using costumes, as in burlesque and drag.

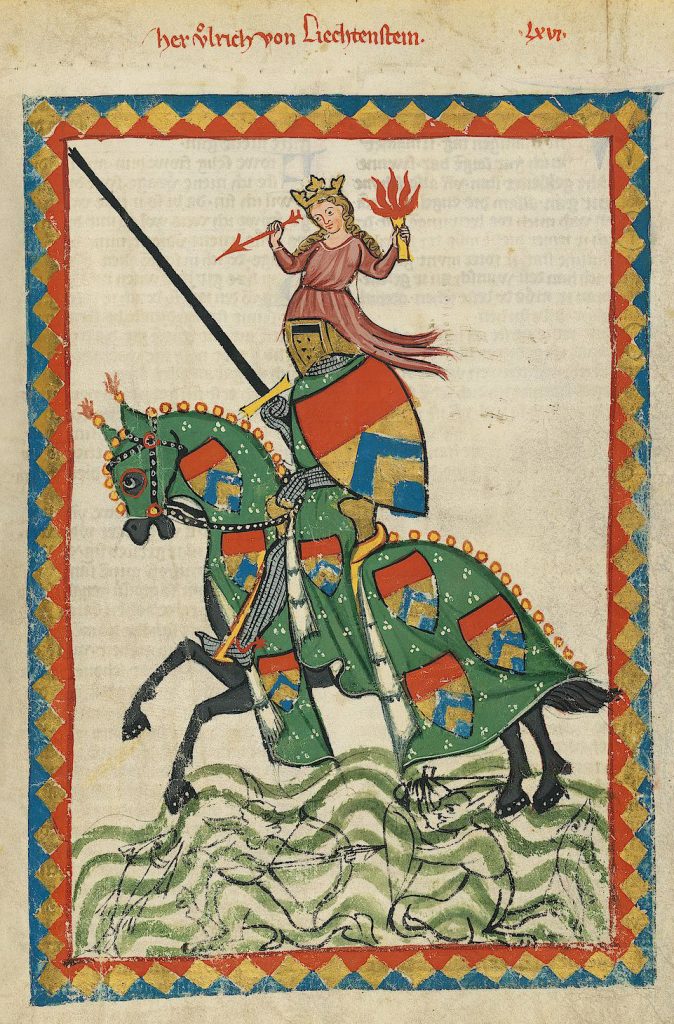

Medieval tournaments provide an excellent opportunity to think about gendered expression. Here, cross-dressing as a form of entertainment, or “drag”, has very old precedents. After considering Nuding’s discussion of early 20th century pageants presenting a playful queer space; medieval tournament could offer a space for playful cross-dressing and as such would be a good opportunity to develop the representation of flexible gender performance in games.14 Ulrich von Liechtenstein performed at tournaments dressed as his female inspiration, Frau Venus, with the gender signifier of long blonde plaits flowing from his helmet.15 Ulrich’s adventures play with cross-dressing and gender. He drew inspiration from King Arthur, an ultra-heroic masculine figure.16 Ulrich also encountered other cross-dressing knights; one dressed as a woman and another dressed as a monk, which provides an example of cross-dressing professions.17 In all these examples, playing martial games offers an opportunity to think about and play with signifiers of gender and profession.

In medieval tournaments, there might also be opportunities for women to subvert martial order by taking over the role of the armed man. In a scathing description of women’s involvement in a 1348 tournament at Berwick-Upon-Tweed, Knighton’s Chronicle describes how women were dressed as men with daggers. Knighton suggests that:

when tournaments were held, at almost every place a troop of ladies would appear, as though they were a company of players, dressed in men’s clothes […] and even with the kind of knives commonly called daggers slung low across their bellies, in pouches.18

While the type of daggers these women took up was not recorded, the description of them and their scandalous placement calls to mind the medieval ballock dagger and its use as a gendered weapon. This obviously phallic-shaped dagger was used by men as a symbol of their knightly virility.19 At this tournament, there is a specific role reversal of martial gendered roles, which provoked outrage from the chronicler. It is not possible to know how realistic this description was, whether Knighton’s outrage was a common opinion or if the women were understood as taking part in a scene of jest or a “dress-up” fantasy during the tournament.

Nonetheless, these women are using male dress and especially arms, to enact a social transgression, as such, occupying a subversive, queer space. Interestingly, there is no mention of punishment for these women and no mention of others’ condemnation. This might suggest that women taking up arms, and subverting these gendered expectations, was not as unusual as might have been supposed. Here, it is possible to see how the tournament may have been a space in which to push the boundaries of cultural norms. Understanding these women’s actions positively or negatively depends on perspective. Knighton presents these disruptive acts as a critique of women. However, a different viewer might here perceive a playful subversion of wider martial culture.

The above examples also reveal how arms and armour do not have to be practical to make a statement about their wielder, especially if the items were made for parades rather than combat. This is important to note because while some video game depictions are realistic, many are not. Instead, some of the unrealistic types of arms and armour offer more creative ways of thinking about characterisation, literally shaping identity through metalwork.

An example to consider here is the game Cyberpunk2077, which may seem odd when considering medievalism. However, the world of Cyberpunk is one where bodies can be altered, and its tropes can be read through ideas found in the medieval past about the divide between the body and armour or weapons. The early medieval text Beowulf questions the hybridity and the limits of the human by blurring the distinction between object and flesh. For instance, Grendel has a sword for an arm and armoured skin.20

Changes to bodies in medieval texts signify those on the periphery or those which might play with normative gender and bodily expectations. For example, in Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Bertilak is transformed magically by a woman into a giant figure of ultra-masculinity. In Cyberpunk 2077, the ‘Mantis Blade’ weapon replaces the forearm with an extendable sword, and the ‘Subdermal Armor’ becomes a protective skin. Such modifications question the extent to which weapons and armour construct the body of a fighter.

Conclusion

To conclude, this blog post has broached three ways of thinking about gender, and in particular queer gender, in medievalist video games. By considering female masculinity, it is possible to reveal the depth of characterisation for female warriors of video games, showing how their gendered depiction can incorporate different aspects of femininity and masculinity alongside their profession. Using the theory of “lesbian-like” it is possible to explore how queer women might traverse multiple gendered spaces in games. Finally, queer body theory reveals how a warrior’s arms or armour construct gender.

Katie Vernon is a PhD candidate in Medieval Studies at the University of York. She researches depictions of arms and armour in Middle English romance (popular medieval adventure stories), focusing on the peripheral social groups. When not working on her PhD, she researches, writes about and runs workshops on the cultural significance of arms and armour in video games and/or such items in museums. You can follow Katie on BlueSky @katievernon.bsky.social and visit her website: katievernon.weebly.com

References

- ‘Queer Medievalisms: A Case Study of Monty Python and the Holy Grail’, in The Cambridge Companion to Medievalism, by Tison Pugh, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2016), 210–23, https://doi.org/10.1017/cco9781316091708.015. 210. ↩︎

- Jack Halberstam, Female Masculinity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478002703. ↩︎

- Rachel Marie Delman, ‘Elite Female Constructions of Power and Space in England, 1444-1541’ (PhD, Oxford, University of Oxford, 2017). ↩︎

- Nancy Bradley Warren and Carolyn P. Collette, ‘“Olde Stories” and Amazons: The Legend of Good Women, the “Knight’s Tale”, and Fourteenth-Century Political Culture’, in The Legend of Good Women: Context and Reception (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2006), 83–104; Rachel M. Delman, ‘Gendered Viewing, Childbirth and Female Authority in the Residence of Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk, at Ewelme, Oxfordshire’, Journal of Medieval History 45, no. 2 (15 March 2019): 181–203, https://doi.org/10.1080/03044181.2019.1593619; Amanda Richardson, ‘Gender and Spacein English Royal Palaces c. 1160—c. 1547: A Study in Access Analysis and Imagery’, Medieval Archaeology 47, no. 1 (June 2003): 131–65, https://doi.org/10.1179/med.2003.47.1.131; Valerie Eads and Rebecca L. R. Garber, ‘Amazon, Allegory, Swordswoman, Saint? The Walpurgis Images in Royal Armouries MS I.33’, in Can These Bones Come to Life?: Insights from Reconstruction, Reenactment, and Re-Creation, ed. Ken Mondschein (Wheaton, Illinois: Freelance Academy Press, 2014), 5–23. ↩︎

- J. Ernst Wülfing, ed., The Laud Troy Book, a Romance Of About 1400 A.D. Now First Edited From the Unique Ms. (Laud Misc. 595) In the Bodleian Library, Oxford, With Introduction, Notes and Glossary By J. Ernst Wülfing, The Early English Text Society (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.–Asher & Co., 1902). ↩︎

- Judith M. Bennett, ‘“Lesbian-Like” and the Social History of Lesbianisms.’, Journal of the History of Sexuality 9, no. 1/2 (2000): 1–24. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- ‘“Hair Cut Short like a Mediæval Page”: Queer Medievalisms in Gwen Lally’s Historical Pageants and Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness (1928)’, in Studies in Medievalism XXXIV, by Emma Nuding (Boydell and Brewer, 2025), 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781805435600-004. ↩︎

- James Lucas, “‘I never wrote that adult women can’t go through them’: The witcher creator addresses Ciri backlash”, The Gamer, https://www.thegamer.com/the-witcher-4-author-andrzej-sapkowski-ciri-backlash-women-trial-of-the-grasses-mutations/ 9/06/2025, accessed 14/06/2025. ↩︎

- Andrzej Sapkowski, Blood of Elves, trans. Danusia Stok (London: Gollancz, 2020). ↩︎

- CD Projekt Red, ‘The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt’ (Poland, 2015). ↩︎

- Judith Butler, Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’, Routledge Classics (London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2011), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203828274; Judith Butler, Undoing Gender, Taylor & Francis eBooks (London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2004), https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203499627. ↩︎

- Cat Stiles, ‘Forgotten Battles: Gender in the Armouries’, accessed 2 May 2025, https://www.heritageopendays.org.uk/resource/forgotten-battles-gender-in-the-armouries.html. ↩︎

- ‘“Hair Cut Short like a Mediæval Page”’. ↩︎

- Ulrich von Liechtenstein, Ulrich von Liechtenstein’s Service of Ladies: An Autobiography, trans. J. W. Thomas, New ed, First Person Singular (Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK ; Rochester, N.Y: Boydell Press, 2004). ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Henry Knighton, Knighton’s Chronicle 1337-1396, ed. G. H. Martin (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995). 93-5. ↩︎

- ‘Forgotten Battles | Royal Armouries’, accessed 2 May 2025, https://royalarmouries.org/objects-and-stories/stories/forgotten-battles. ↩︎

- Megan Cavell, ‘Constructing the Monstrous Body in Beowulf’, Anglo-Saxon England 43 (December 2014): 155–81, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0263675114000064. ↩︎